In the week of his 55th birthday, Mr John Davey contracted meningococcal disease, and was put into an induced coma to be treated with drugs at Knox Hospital in Melbourne’s East.

Within another week or so, he contracted sepsis while in his induced coma.

“My first introduction to septicaemia was when I awoke from the coma and realised that my extremities: my feet, legs and hands were black and dead,” Mr Davey said.

“As I was told they were literally dead weight.

“Welcome to septicaemia world.”

A few years later, Mr Davey, a quadruple amputee, has gone through rigorous physiotherapy to allow him to adjust to his new body.

Sepsis and septic shock

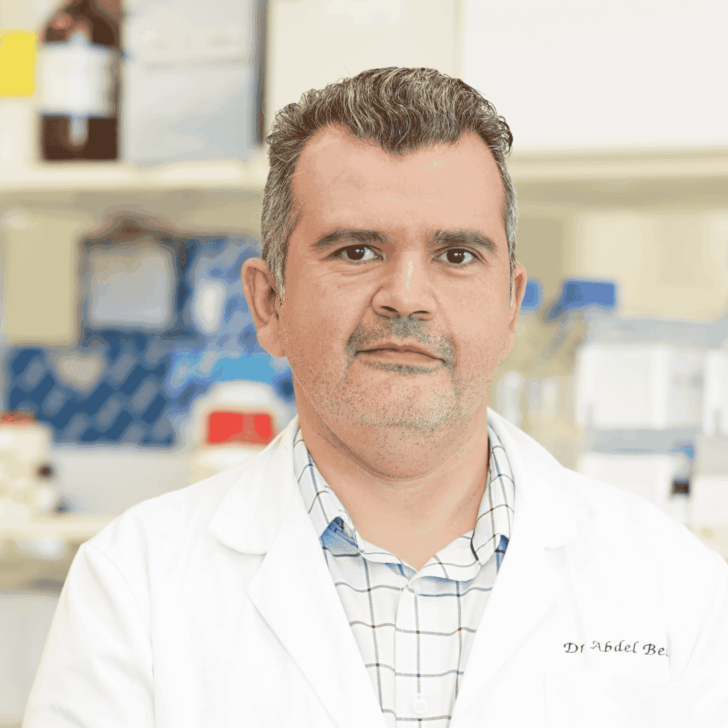

Associate Professor Yugeesh Lankadeva, who leads the Translational Cardiovascular and Renal Research Group and the Systems Neuroscience Theme at The Florey, said sepsis is notoriously difficult to treat and is often deadly.

“Sepsis accounts for 35–50 percent of all hospital deaths. It occurs when the immune system fails to fight off an underlying infection, causing excessive inflammation, life-threatening falls in blood pressure, multiple organ failure, and death,” Associate Professor Lankadeva said.

According to the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, each year, 55,000 Australians are diagnosed with sepsis and more than 8,700 lose their lives.

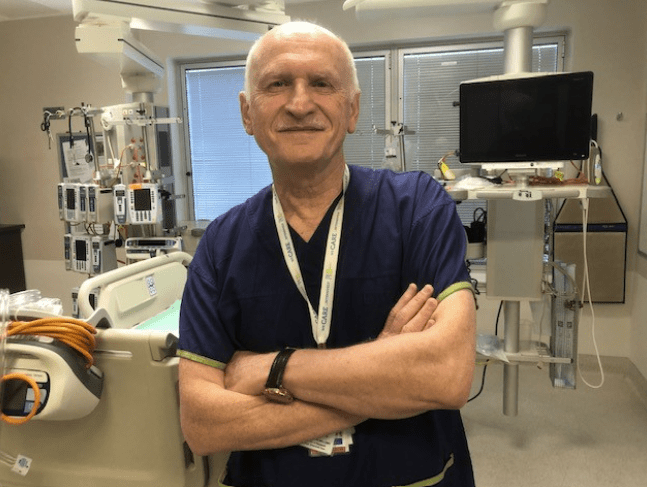

Professor Rinaldo Bellomo, Austin Hospital’s Director of Intensive Care Research, said that sepsis is the biggest killer in intensive care units in Australia and worldwide.

“It often develops so quickly that patients are already critically ill by the time they reach us,” he said.

In many ways, Mr Davey could be considered lucky to be alive, despite the radical transformation his body has undergone through his amputations.

‘Remarkable’ treatment for sepsis

Currently, there aren’t any treatments that reverse the detrimental effects of sepsis on the vital organs.

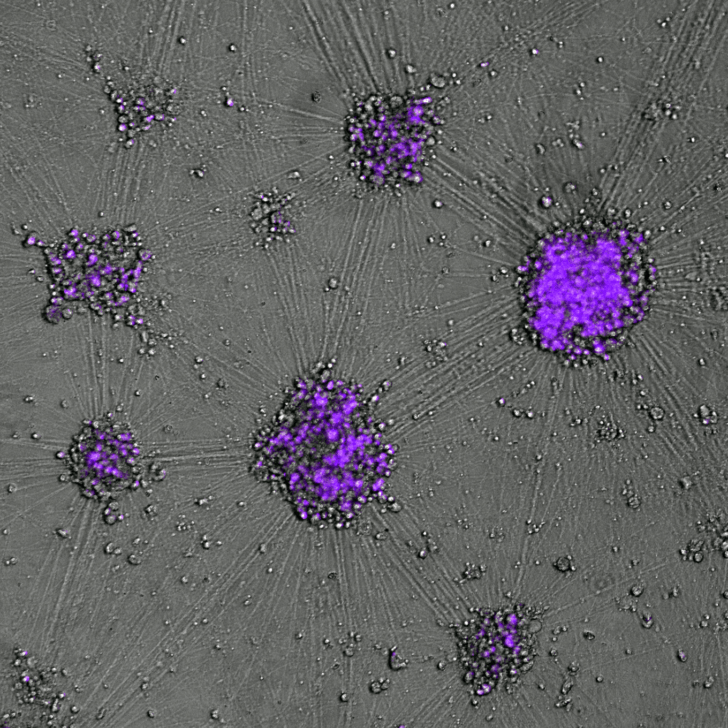

Two of the main detrimental effects of sepsis are delirium and acute kidney injury, and frequently cognitive impairment and chronic kidney injury in survivors of sepsis. Over the years, the Florey researchers have demonstrated that there are large decreases in the levels of oxygen in the brain and kidneys during sepsis and they believe these changes are the causes of the failure of these vital organs.

Associate Professor Yugeesh Lankadeva, Professors Clive May and Rinaldo Bellomo are now developing a new treatment, which is the first ever to actually improve multiple organ health and restore normal physiological functions.

Interestingly, they found that intravenous sodium ascorbate normalised the oxygen levels in the brain and kidneys and reduced requirements for blood pressure maintaining drugs in their preclinical model of sepsis. The organs then started to work again and within 3-4 hours the clinical state dramatically improved.

“We have studied many drugs over the last 20 years to try and develop new better treatments for sepsis, none of which have had much benefit,” Professor Clive May, from the Florey’s Preclinical Critical Care Unit, said.

The beneficial effect of sodium ascorbate is quite remarkable.

It is thought that one of the main causes of organ failure that occurs in sepsis is oxidative stress and inflammation that occurs during sepsis and septic shock.

The researchers therefore started to examine different compounds and drugs that could reverse this effect, initially by using a drug called Tempol. They found that if Tempol was administered directly into the kidney, the kidney failure was reversed and the kidneys started to work normally. However, when Tempol was given intravenously, it did not produce the same effect.

Around this time there were clinical studies looking at relatively low doses of Vitamin C, but the results from these studies were inconsistent with both beneficial and detrimental effects being reported. Because of these inconsistent results the use of Vitamin C as a treatment for sepsis remains controversial. There is, however, evidence that very high doses of Vitamin C can be given to patients with cancer without severe side effects.

However, such very high doses could not be studied in critically ill septic patients for ethical reasons. The Florey researchers therefore used their pre-clinical model of sepsis enabling investigation of what they call ‘megadoses’, and instead of using Vitamin C which is an acidic compound, they chose instead to use a pH-balanced formulation of it: sodium ascorbate. By infusing these megadoses of sodium ascorbate directly into the bloodstream, they discovered that it rapidly and completely reversed all the pathophysiological effects of sepsis.

The team recently completed a Phase Ia double-blind randomised placebo controlled clinical trial in 30 septic patients at Austin Health to demonstrate feasibility and physiological signals of benefit of using intravenous sodium ascorbate. For ethical reasons a lower dose of sodium ascorbate was used, with plans to use a megadose in subsequent clinical trials.

“We’ve seen quite promising signals translate from bench-to-bedside, which really puts us at the vanguard, to really advance this treatment into larger multi-centre clinical trials across mainland Australia to see how effectively this drug works in patients with septic shock,” Associate Professor Yugeesh Lankadeva said.

A potentially ‘world-changing’ infusion

“What John has described is what happens to so many patients with sepsis. The state-of-the-art drugs that are currently given to septic patients really aim just to keep you alive with the hope that eventually your body will recover. They do not reverse the effect of sepsis,” Professor Clive May said.

“The problem has been that there haven’t been any treatments that reverse the organ damage that occurs with sepsis.”

This is what’s so exciting about megadose sodium ascorbate. We believe that it will cure sepsis that is induced by bacteria and by viruses.

Mr Davey recalls: “My wife watched it all. The five heart attacks, calling my children, flying them over to say goodbye to dad.”

“I thought that was the end of it, but what I learned was that the septicaemia hadn’t actually stopped. And [the doctors] kept talking about demarcation.”

This is when the body is still deciding what is ‘dead’ and what is going to live and to therefore indicate to doctors when and where on the body the amputation should take place. While his other symptoms from his meningococcal had been clearing, his skin continued to deteriorate.

Although it is now too late for Mr Davey to have the infusion, he says what the Florey researchers are doing is life-changing.

“It’s not just life-changing, it’s world-changing, and wow that’s just incredible,” Mr Davey said.

“We’ve seen dramatic results in our preclinical studies of sepsis, where megadoses of sodium ascorbate resulted in full recovery within just three hours, with no side effects. It’s heartening to see all those years of painstaking research pay off with a treatment now within reach for patients,” Professor Clive May said.

The researchers also say that sodium ascorbate is affordable and readily available, leading to more rapid clinical uptake in low-income countries which bear the largest burden of sepsis.