Professor Anne-Louise Ponsonby is a renowned epidemiologist and public health physician. She has extensive experience in the design, conduct and analysis of population-based studies, for public health benefits.

As a Division Head within the Florey, Professor Anne-Louise Ponsonby is currently doing invaluable work, in particular, investigating key issues relating to the adverse impact of exposure to modern chemicals on brain development in early life. In addition, she is also looking at how environments can contribute to multiple sclerosis.

“My goal is to generate new evidence in these disease areas and contribute to better preventions,” she explains.

Already measurable progress has been made contributing to the way researchers and health practitioners understand, treat and prevent conditions in many disease areas.

“My work so far has informed Australian and international public health policies and preventative guidelines, bringing benefits to people across the globe. My work demonstrates the power of epidemiological studies for understanding diseases.”

Here are two questions we put to Professor Ponsonby:

As an epidemiologist, public health physician, and clinical researcher, what was the biggest research milestone you have achieved in your Florey career? What was that outcome? And how did you transform people’s lives directly or indirectly?

Discovering new knowledge can change national and international guidelines and make a significant social impact. I was part of pioneering research into sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), which has lasting impacts today.”

My role was Co-Principal Investigator of a large birth study of over 10,000 infants, which generated new knowledge and guidelines for SIDS. The outcome of this major investigation included findings on safe sleeping positions and environments.

Then in 2013 it was wonderful when the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported a decline in SIDS incidence rates by 80% over the 22 year period from 1990 to 2012 following our recommendations.

Remarkably, SIDS deaths fell from almost two per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 0.2 per 1,000 live births in 2012. The reality is that knowledge is key, particularly where the knowledge is collected from credible research, and that’s how we make a difference.

What are the strengths of The Florey that attracted you? And how does that strength reinforce our position as Australia’s leading neuroscience research institute?

With all the research carried out at The Florey, the aim at all times is to include the latest technologies, such as neuro-imaging as well as the newest data science methods. No matter what the particular challenge we are working on, we always want to ensure we are taking full advantage of the very latest advances in research data generation and analytics.

With a rich history of achievement going back to the 1960s, The Florey is a medical research institute with a long tradition of discovery. The focus is on understanding the fundamental cause and underlying mechanism of diseases and the healthy brain.

Our approach aligns very well with my personal view that for many diseases, the best way to prevent and treat brain and mind disorders is to understand how they are caused. If you can do that, you can then design appropriate interventions, including the very early beginnings of disease.

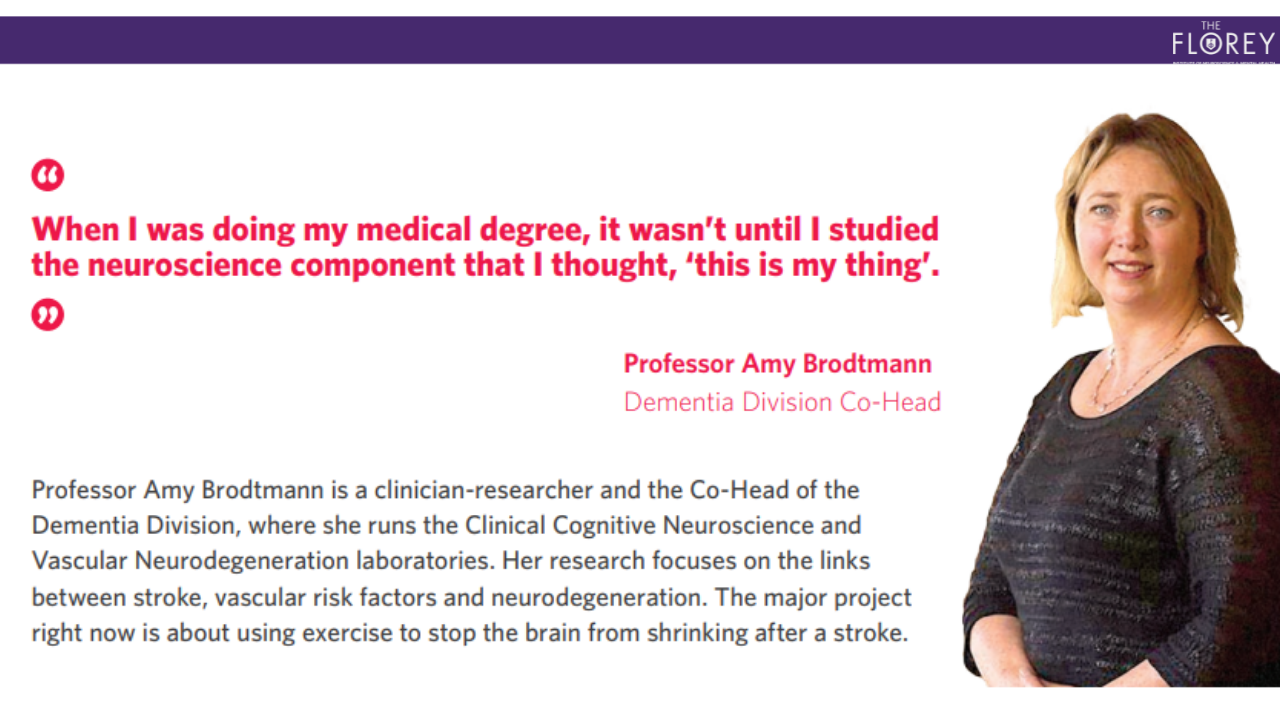

For someone who has suffered a stroke and is experiencing a poorer quality of life, can the learnings from your project make a difference?

Well, that’s exactly what we’re testing and hoping for. I’d like to develop a simple exercise program that we give once people have finished normal rehab. The aim would be that this exercise regime would increase the brain’s reserve, while also slowing down the degenerative process, improving their mood, their fitness, their quality of life, and hopefully their cognitive performance.

Is this exercise intervention to be performed at home, or will the stroke patient need to go to a rehab centre and be guided by clinicians?

We are comparing two different possible types. Both are delivered in the patient’s home, with the guidance of a qualified trainer monitoring that person via Zoom. Essentially, it is Zoom Delivered Intervention Against Cognitive decline (“ZODIAC”). What we are working on is being able to offer classes with a trainer for people who have had a stroke. All the exercise would be at home for, say, an 8-week program. It would be like cardiac rehab, but instead of coming into the hospital or going to the gym, they can participate from home.

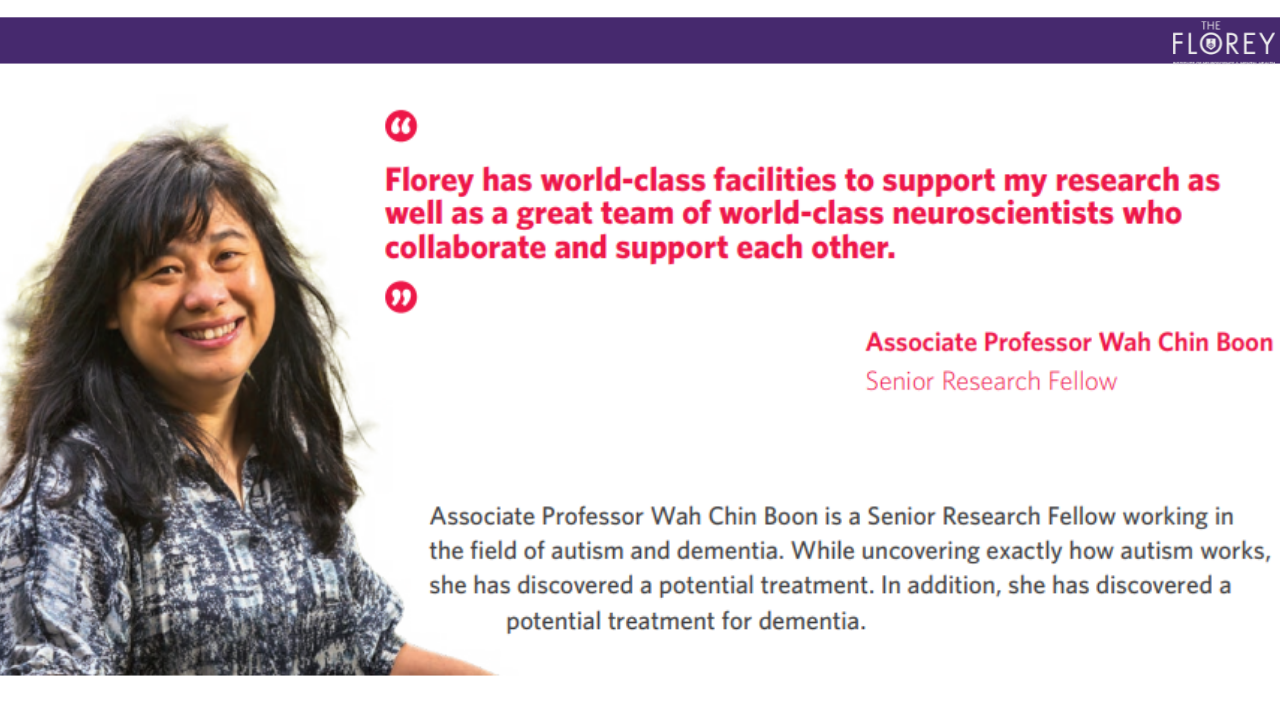

What is the project you are working on, and how will that make a difference in improving the quality of life for someone with the associated neurodevelopment/disorder?

Right now, I am working on understanding what contributes to disorders such as autism. As I was examining the underlying mechanism of autism, I discovered a potential treatment, which has gained patent approval from the USA, the European Union and Australia. However, due to the COVID-19 disruptions over the last two years, it has been difficult to seek funding to progress to clinical trials.

In addition, I am pleased to report that I have also discovered a potential treatment for dementia, which has been licensed to a commercial partner.

Have you always known that you would be a researcher? What kept you going?

Yes, I have wanted to be a scientist since I was three years old. I was amazed by ants in my mum’s kitchen and fish in the little aquarium. I performed short experiments, and realised ants cannot live in water and fish cannot live out of water.

By understanding the mechanisms that lead to a disorder, we can identify therapeutic targets. I may have achieved that for autism and dementia, I hope these treatments can be tested in clinical trials. And then I certainly will try to do the same for other disorders such as OCD and schizophrenia.

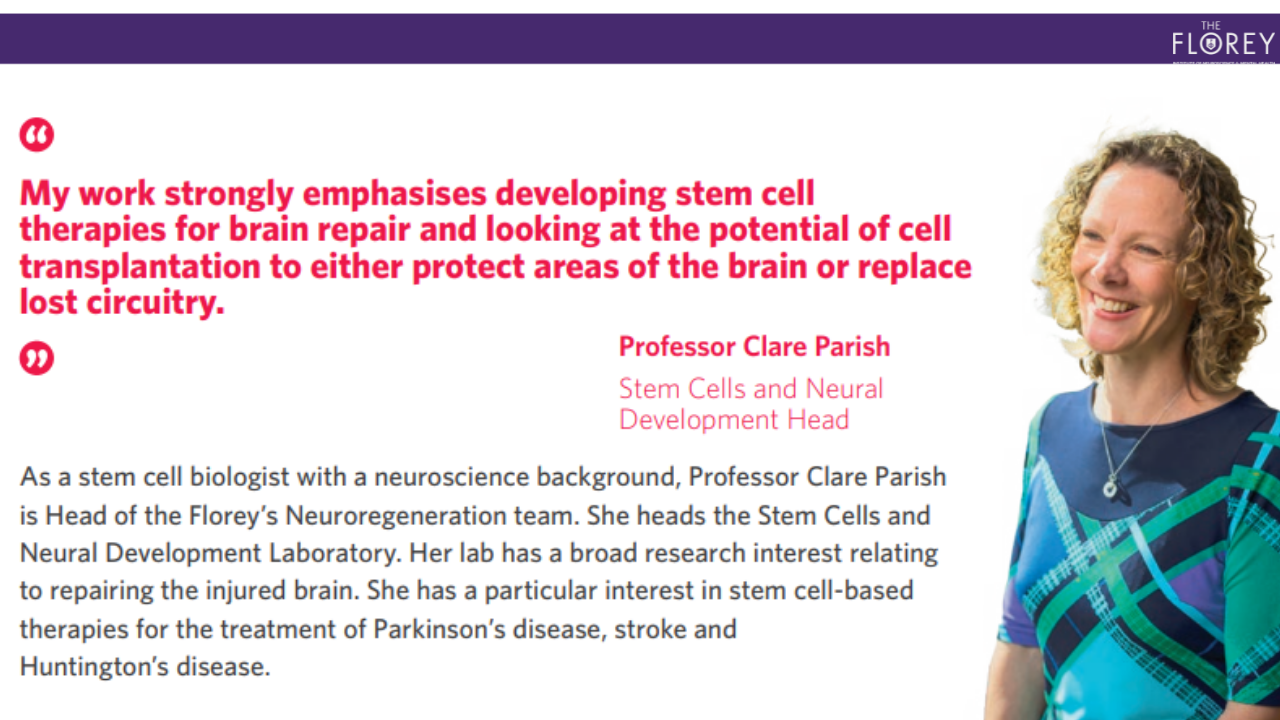

What is something exciting that you’re working on right now?

We’ve had several significant successes in the last couple of years, particularly in the space of advancing stem cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease.

The idea here is that you’re transplanting back into the brain the cell type that dies within the disease, and it’s been known for some time that this has been feasible, and they’re just now starting to launch clinical trials using human stem cells. As of now, we’re applying the next level of technology for this therapy. And we’ve also developed a combined cell and gene therapy approach for the purpose of promoting connectivity-based transplants.

What advice would you give to an aspiring female researcher, especially someone who has limited experience, such as a university graduate?

I often say to people I mentor: you want a diverse group of people as your mentors. You want someone who reflects who you are as a woman. Nobody understands juggling domestic and work-life as a mother does.

Find someone you admire in terms of how they have strategically driven their career. The first one is a woman, and the other is someone who you decide you look up to.