- A dedicated team of scientists at the Florey including Professor Kevin Barnham and Dr Leah Beauchamp are pioneering new approaches to diagnose and treat Parkinson’s disease.

- The scientists are also examining the potential link between COVID-19 and increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Early diagnosis key to moving forward in Parkinson’s

According to Professor Barnham shifting the way we think about and approach the disease is essential to tackling Parkinson’s.

“A diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in the clinical setting currently relies on the person presenting with movement dysfunction, but research shows that 50-70% of dopamine cell loss in the brain has already occurred by this time. Waiting until this stage to diagnose and treat Parkinson’s disease means you’ve probably already missed the window for neuroprotective therapies to have their intended effect,” explained Professor Barnham.

He continued, “I liken the manifestation of Parkinson’s to a bomb with a really long fuse which we think is about ten to twenty years long and by the time we see people present in the clinic the bomb has already exploded. While excellent treatments are available to manage symptoms, our work is trying to understand the fuse and what can be done to disarm it well ahead of time,” he said.

Parkinson’s may have once been thought of as a disease of old age, but what we’re now starting to realise is that it’s more likely starting in middle-age.

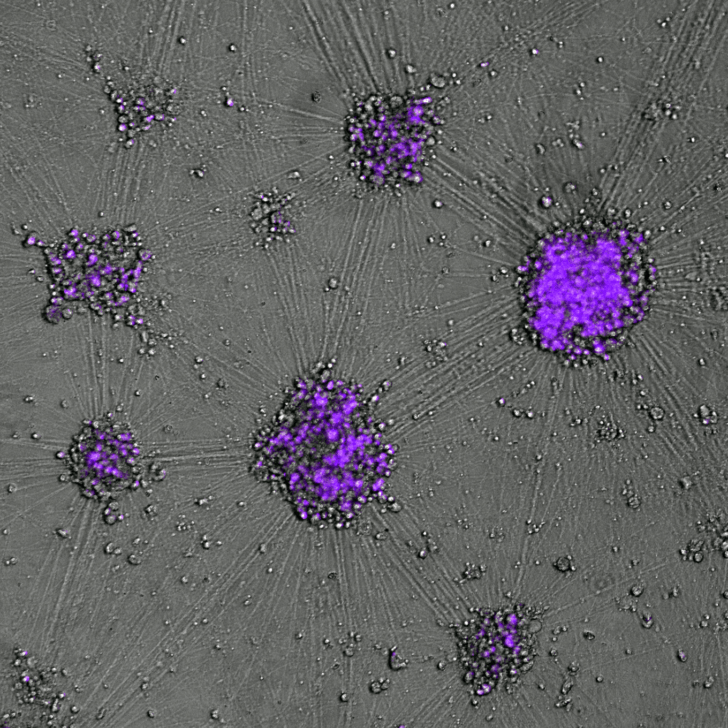

The research group believe olfaction changes could be amid signs that the fuse is lit.

“Loss of smell or reduced smell is a symptom that presents in around 90% of people in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease and about a decade ahead of motor symptoms. We believe this symptom could present a new way forward in detecting someone’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease much early then what happens currently,” said Dr Leah Beauchamp.

The team, which also includes Professor David Finkelstein and Professor Ashley Bush and their clinical collaborator and neurologist, Dr Andrew Evans, have been considering new measures to be able to diagnose Parkinson’s easier and earlier.

Among these is a simple, cost-effective screening protocol which they hope can be used to identify people in the community at risk of developing Parkinson’s, or who are in early stages of the disease, at a time when therapies have the greatest potential to prevent disease progression and onset of movement dysfunction.

In 2020, Florey researchers published critical new findings suggesting that that people with REM sleep behaviour disorder have prodromal, or early-stage, Parkinson’s disease. The team believe that this cohort represents an ideal group of people to participate in clinical trials of neuroprotective therapies as they have a higher predisposition to go on to develop the disease, but don’t have the same level of dopamine cell loss in the brain as people in later stages of Parkinson’s. Put simply, neuroprotective therapies, including the two treatments developed by Florey researchers under clinical investigation, may be able to better deliver their intended effects to this cohort.

Professor Barnham reflects on the way forward. “I’m reminded of NASA and what is seen as one of the greatest achievements of the twentieth century. There was no scientific impediment stopping NASA going to the moon. They got there because they decided to go. It’s as simple as that. We can prevent Parkinson’s disease if as a society we decide to make that commitment.”

Parkinson’s expertise leads to neurological warning signs of COVID-19

When reports of loss of smell in people infected with coronavirus started surfacing in early 2020, it set off red flags for The Florey’s Parkinson’s researchers. They began investigating the scope of neurological symptoms associated with the virus and were among the first in the world to publish a review paper warning of the possible long-term neurological consequences of COVID-19.

“We found that neurological symptoms being reported ranged from rare, such as lack of oxygen to the brain known as brain hypoxia, to more common symptoms such as loss of smell which was on average reported in three out of four people infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” said Dr Beauchamp.

“While on the surface loss of smell or reduced smell can appear as little cause for concern, it actually tells us that acutely there is inflammation occurring in the olfactory system,” she explained.

Inflammation is considered to play a major role in the pathogenesis of neurogenerative disease. It has been particularly well studied in Parkinson’s, among a mosaic of genetic and environmental factors understood to increase one’s risk of developing the disease.

Research now suggests that in the years following the last global viral pandemic, the Spanish Flu in 1918, the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease increased two to three-fold worldwide.

“We should take this insight from the Spanish Flu and take action to prevent a neurological wave of diseases that could possibly unfold down track as a result of the coronavirus”, said Professor Barnham.

“It is incredibly concerning to think that the incidence of Parkinson’s disease is already set to double in the next 20 years with no disease-modifying treatments available, before even considering potential effects of COVID-19,” he said.

The world was caught off guard the first-time, but it doesn’t need to be again. We now know what needs to be done. Alongside a strategised public health approach, tools for early diagnosis and better treatments are key.