- This International Women’s Day, we speak to 3 scientists at The Florey who are studying conditions that largely affect women.

- Dr Nicole Jenkins, Dr Francesca Alves and PhD candidate Lauren Ursich each speak about their research, and the importance of gender representation in every career stage in science.

- By supporting women in science we allow for research that can lead us to better health outcomes for women in the future.

Levelling up for science and health

What can change for women’s health outcomes and care when women are represented and supported in the scientific field today?

In honour of International Women’s Day, we speak to 3 scientists at The Florey at different stages in their career – PhD candidate Lauren Ursich, early-career researcher Dr Francesca Alves and Senior Research Officer Dr Nicole Jenkins.

Ms Ursich, Dr Alves and Dr Jenkins are currently studying areas and conditions that largely affect women. However, the nature of these conditions and the impact they have on women and individuals have been historically underrepresented.

Today, we hear about each of their journeys into science, the potential impact of their research, and what they hope to see in the future for women pursuing careers in the scientific field.

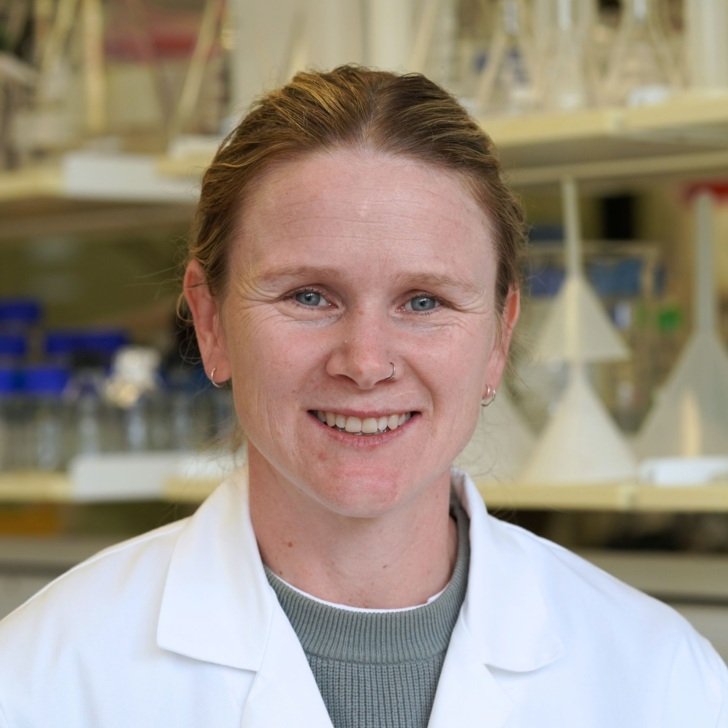

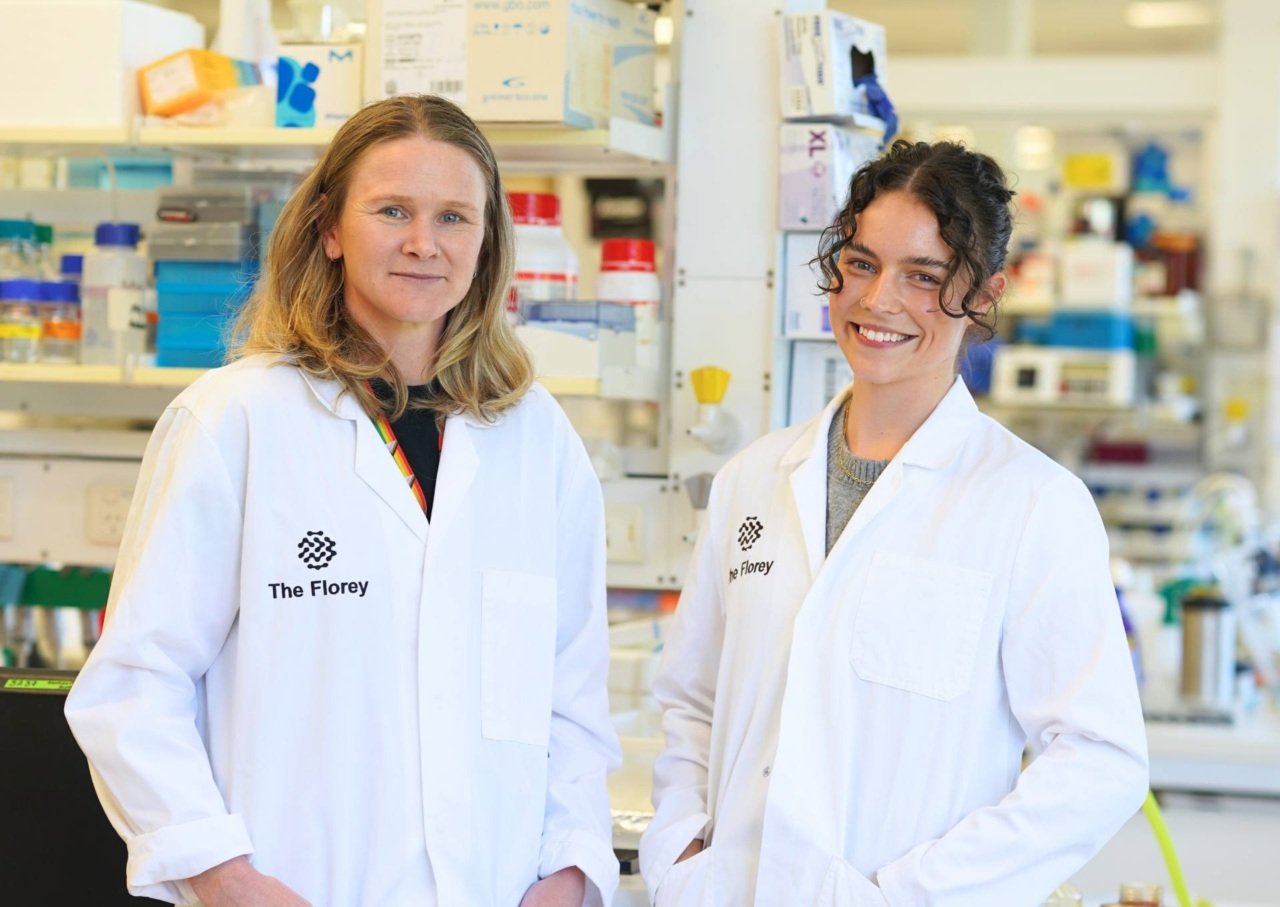

Lauren Ursich, Addiction Neuroscience Group

Lauren Ursich, PhD candidate in our Addiction Neuroscience Lab, is studying how addiction affects the female brain alongside Dr Leigh Walker and Professor Andrew Lawrence.

“It’s always been science for me,” Lauren says.

“First, there’s a personal connection – I’ve watched a lot of women in my life work their way unsuccessfully through all of the available treatments for alcohol use disorder.”

The second element is Lauren’s passion towards promoting sex and gender diversity in research.

She currently works closely with Dr Leigh Walker, senior researcher at The Florey studying how sex differences modulate anxiety and binge-drinking behaviours.

Despite the fact that alcohol use disorder is a rising issue, sex has been largely ignored in preclinical research and drug development. Dr Walker and her team are changing this, leading our research into excessive alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders in women by including female models in their research.

“Leigh is an incredible scientist, a great leader and a really great person to work with, but there is so much power in seeing your identity represented in leadership, particularly in science,” Lauren says.

It was once that I saw my identity in her leadership, as a woman and a queer woman, that’s when I’ve really grown as a scientist and leader into my research and my career.

The team’s research now works to uncover the underlying biology of addiction in the female brain, which can lead to creating more targeted therapies.

Dr Francesca Alves, Translational Neurodegeneration Group

Dr Francesca Alves, Research Fellow in our Translational Neurodegeneration Group, is investigating the underlying mechanisms of energy deficiency in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Around 75% of people who live with ME/CFS are women.

“This illness can affect people of all ages, all demographics, but what we know is that the main cohort of people that have this illness are women,” Dr Alves says.

“We don’t know the causes of why this illness predominantly affects women, but we know that it’s misunderstood, and there’s a lot of stigma associated with it.”

Dr Alves hopes that her research may shed light and remove the stigma, leading to new therapeutics that may help women and individuals affected by ME/CFS.

As an early-career researcher, Dr Alves emphasises the need for more representation of women in the later stages of a career in research.

“When I started my PhD approximately 6 years ago, I had 4 male group leaders as supervisors, I had a male Chair, I had a male Head of Department,” Dr Alves says.

“What I found is that there was this gap in a career trajectory where women almost seem to drop off at a certain stage.”

In the future, I hope that a woman that starts her PhD can see a woman at every stage in the career trajectory. She can see that a woman that’s a professor is not an exception, it’s a norm. That there’s no limitations in their decisions of their career and life outside of science.

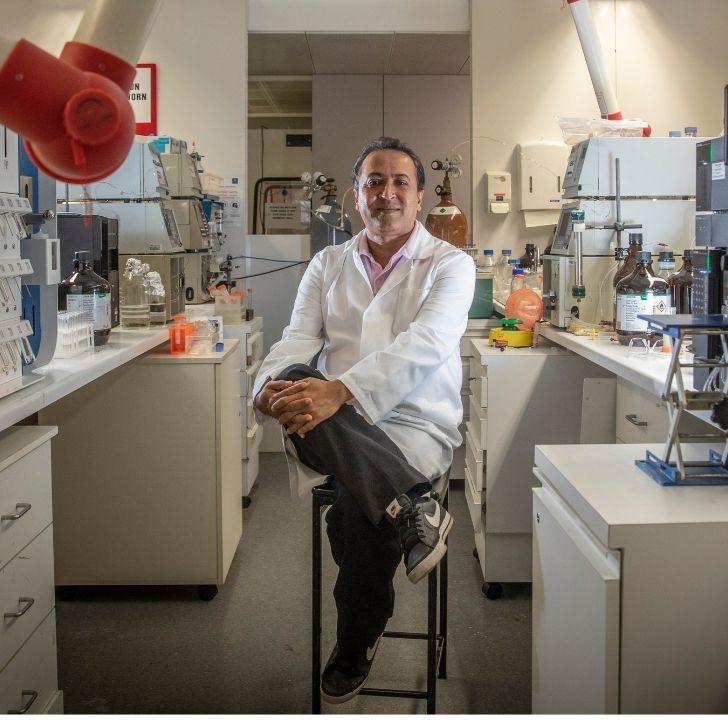

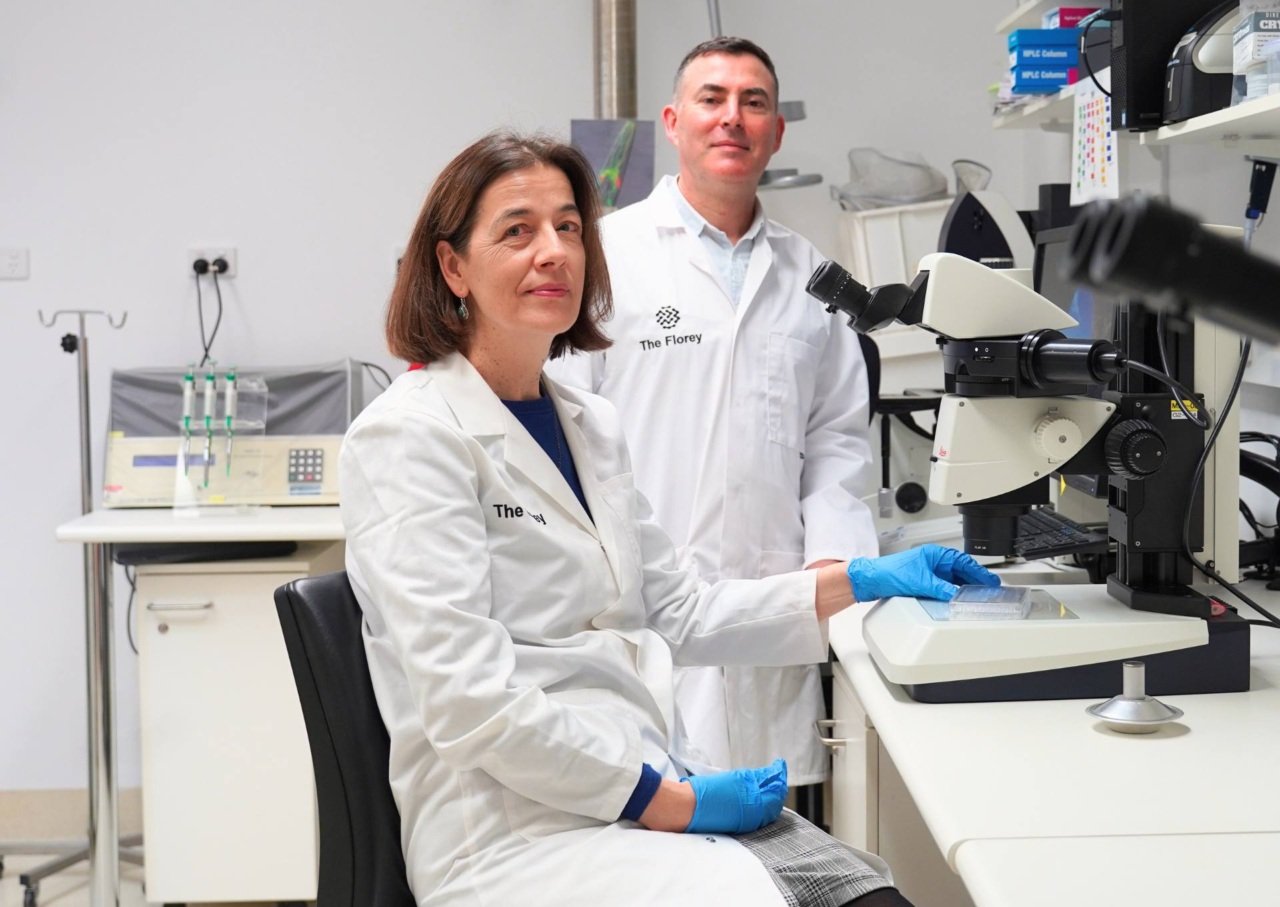

Dr Nicole Jenkins, FeBI Technologies

Dr Nicole Jenkins is CEO and Co-founder of FeBI Technologies, a startup company working to revolutionise the diagnosis and management of iron disorders, which affect 1 in 5 women in Australia, and 1 in 3 premenopausal women.

Iron levels are important for health and wellbeing, but more than 2 billion people worldwide have an iron disorder.

Recent research found that up to 35% of women with an iron deficiency were initially misdiagnosed and treated for the wrong condition.

“The most common misdiagnosis is depression,” Dr Jenkins says. “So these women didn’t have depression but were treated for depression.”

I’ve been working in the lab on the importance of iron in ageing and neurodegeneration for a number of years, but I also had an iron disorder. It took 7 years for me to be correctly diagnosed and treated.

The experience helped Dr Jenkins understand the clinical challenges that come with the diagnosis and management of iron status. These challenges are prevalent especially for people with chronic health conditions.

“At FeBI Technologies, our aim is to revolutionise the diagnosis and management of iron disorders using some exciting new quantum technology,” Dr Jenkins says.

She describes one of the most rewarding parts of being CEO of FeBI Technologies as being able to engage with the potential end-users and clinicians who would benefit from their technology. This has helped her to understand the importance of a better solution, particularly for women.

Across the years, Dr Jenkins has seen the decreasing number of women the higher up you go in the career stages of science.

“At the early career stages, we have around 50% – so a good gender balance. But by the time we get to associate Professor and professor, it’s really small.”

Dr Jenkins took a 9-year break from her science career to raise her family. When she returned, she worked on providing career support for women researchers – focusing on grant programs to help women returning to science after a career break.

“What I’m seeing is fantastic science, great grantsmanship, people really worthy of funding that are just missing out,” Dr Jenkins says.

I find that really heartbreaking, as I know that there is amazing science that could be being done across the board, particularly by women.

Dr Jenkins says she would love to see more philanthropic donations or improved grant funding, which would enable more of this research to take place.

“We are driven by that passion to make the world a better place,” Dr Jenkins says. “That’s the driving force behind everything that we do.”