- Patricia Wongsodirdjo and Thomas Nguyen are PhD candidates working in The Florey’s Dementia Mission.

- Patricia’s and Thomas’ interest in Alzheimer’s disease began in high school, when they both saw their families suffer the impact of dementia.

- Their research will now contribute towards early prevention strategies and a new generation of therapeutics for dementia.

“She can still play the piano.”

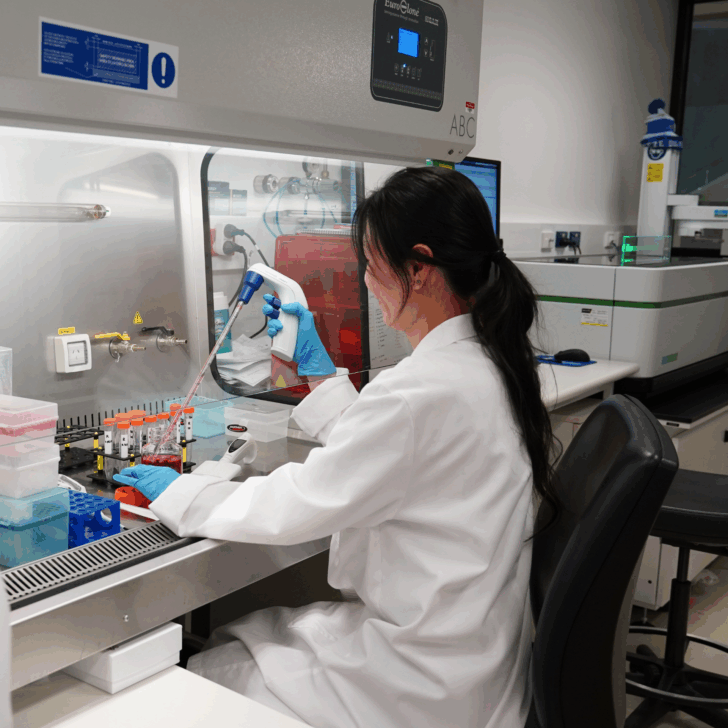

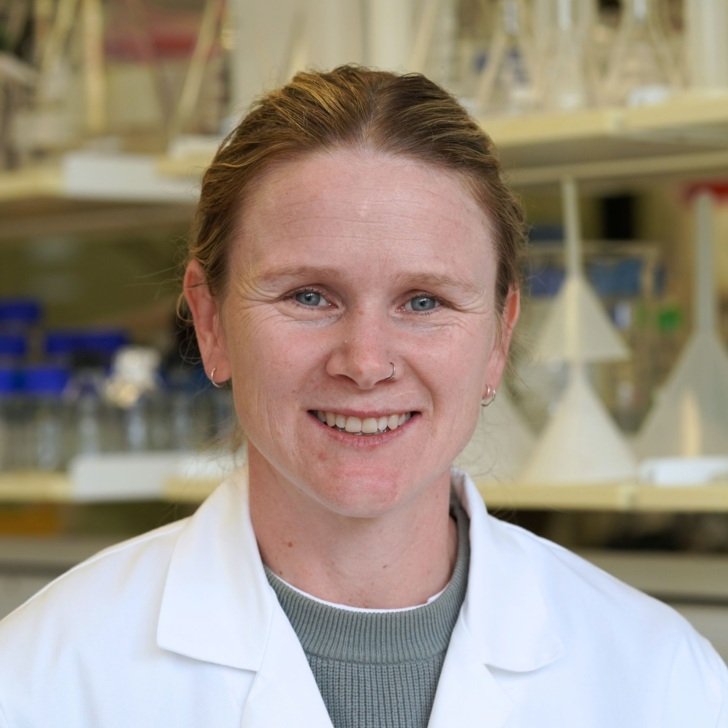

Florey PhD student Patricia Wongsodirdjo always knew she wanted to study dementia drug development when pursuing her career.

Working under the supervision of Dr Rebecca Nisbet and Dr Laura Vella in The Florey’s Dementia Mission, Patricia has now been studying Alzheimer’s disease for the past 3 years.

The main reason I wanted to pursue research, especially in the development of Alzheimer’s therapeutics, was driven by my frustration of the ineffective treatments given to my great aunt and grandma.

Patricia’s family became caretakers of her great aunt when Patricia was still in high school.

“It was especially difficult for us,” she says. “We took her to see doctors, but the best treatment available at the time was mostly palliative, which didn’t improve her condition.”

Treatments were expensive and prescribed over a long period of time, costing the family more money to maintain.

“It was also hard to get her to take the medicine, so there are challenges even with giving the patients the medicine, and it’s especially challenging when it doesn’t work.”

Patricia’s great aunt passed away in 2019 after battling the disease.

Today, Patricia’s family takes care of her grandmother, who is living with late onset symptoms of dementia.

“She is an amazing lady and growing up, she was trained to be a piano teacher,” Patricia says.

While her grandma studied the piano, Patricia’s grandpa was trained on the violin. They met as teachers and continued playing after they were married.

She still can play the piano, which is really impressive. But she doesn’t remember her favourite pieces.

“I witnessed her condition deteriorate rapidly.”

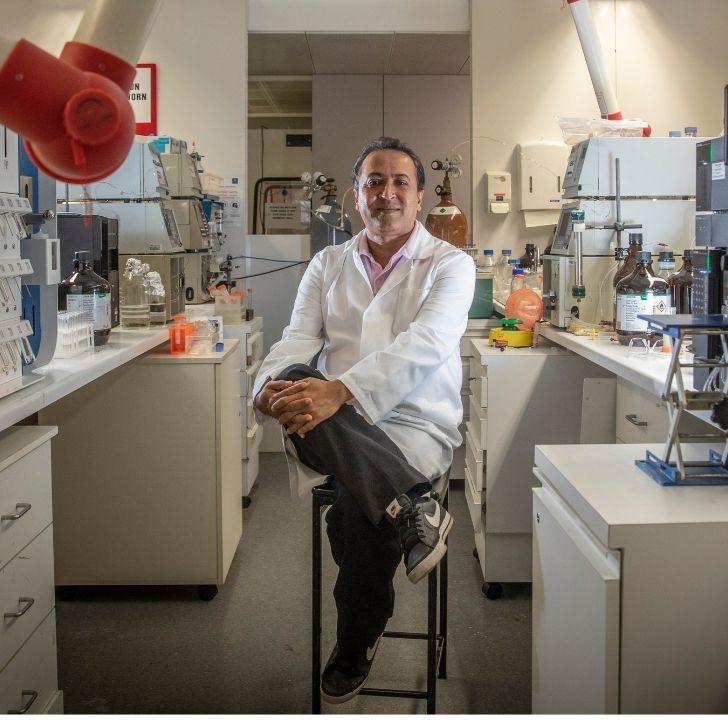

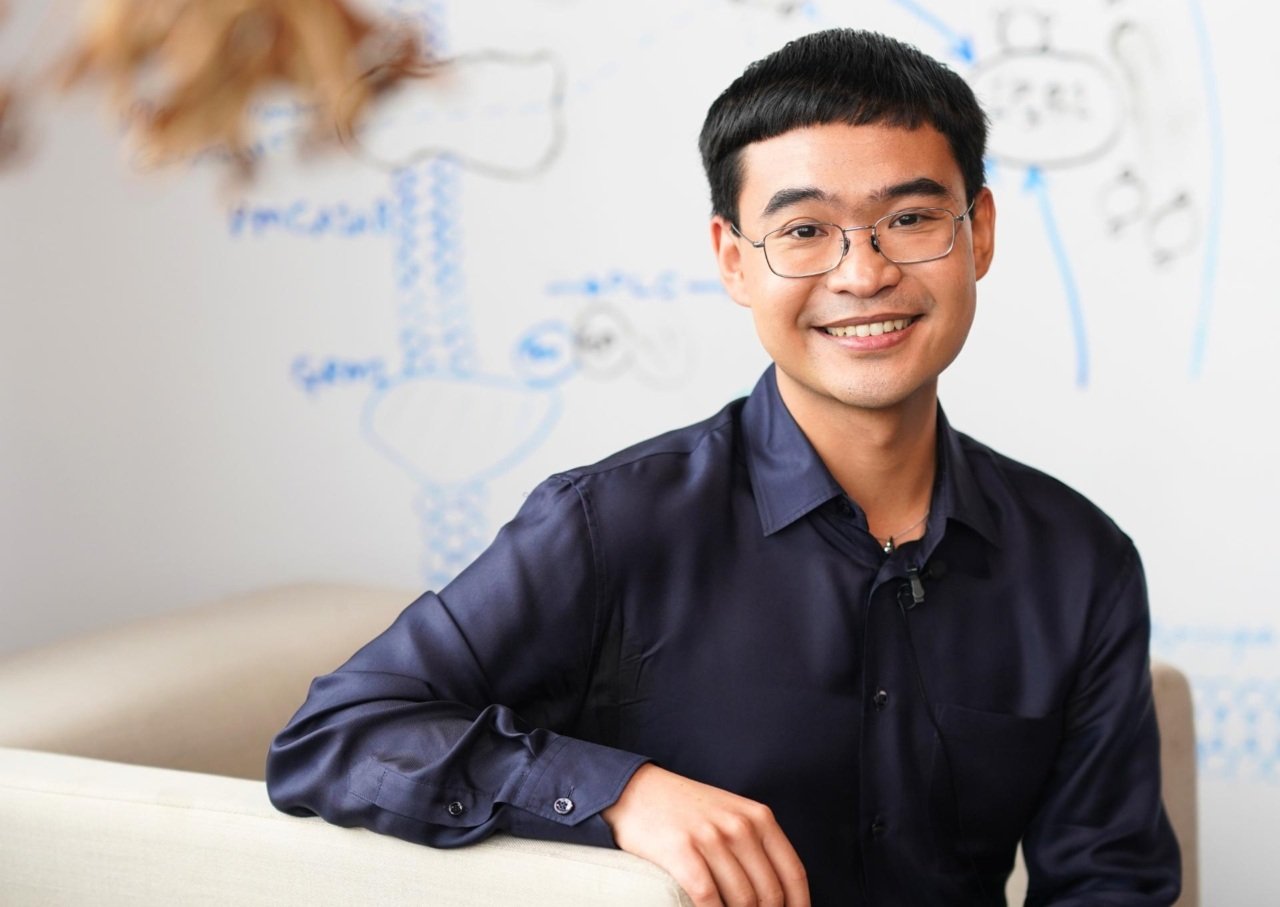

A similar experience happened to Thomas Nguyen, a Florey PhD candidate now working under the supervision of Professor Scott Ayton, Research Lead of The Florey’s Dementia Mission.

“The research question that I am trying to answer is how the neurons are dying,” Thomas says.

Thomas’ great passion for neuroscience stems from wanting to study the universe, almost the way astronomers do.

As a neuroscientist in training, I am studying the universe within each of us that is the interconnected network of the neurons in the brain, and I think that’s beautiful.

Similar to Patricia, Thomas’ grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease when he was just in high school.

Thomas says the disease transformed his grandmother from someone caring and fun to a completely different person.

“I witnessed her condition deteriorate so rapidly,” Thomas recalls. “I felt sad, frustrated, scared and hopeless as a high school boy.”

Patricia also had a close relationship with her grandmother – who was always supportive of the family and would help pick the grandchildren up from school.

“My grandma is in her 80s, so you already would expect some memory loss at that stage. But the memory loss we observed was just exponential, it was not physiological memory loss that you would expect with other elderly individuals.”

Patricia says her grandmother’s condition became “really, really pronounced” after she lost her sister, Patricia’s great aunt, from Alzheimer’s disease.

“It was challenging for me to see how this disease reduced her personality. It’s a devastating disease both for the patient as well as the caretakers.”

The hope today

Thomas’ experience became a motivating factor behind his journey of understanding Alzheimer’s disease.

Once you can understand how the brain cells die, you can then develop effective therapeutic interventions to either prevent or delay the disease from progressing.

Similarly, the frustration Patricia experienced also drove her to pursue drug development. She initially majored in pharmacology and later came across Dr Nisbet’s lab, which specialised in Alzheimer’s disease treatments.

“I got really excited because what she was working on, I believe it’s at the forefront of Alzheimer’s therapeutics,” Patricia explains.

Some of her work with Dr Nisbet included unlocking how to use mRNA to target Alzheimer’s disease.

I’m very excited, especially with what our group is doing, because no- one has explored using mRNA therapeutics in the context of Alzheimer’s treatments before.

“We are also looking at strategies to help deliver drugs effectively into the brain,” Patricia says. “That’s actually the main problem with these treatments is that they don’t get into the brain as easily as we want it to.”

When asked about her supervisors Dr Nisbet and Dr Vella, Patricia says, “They are superheroes to me.”

“Their minds are so brilliant, they have all these ideas and they get to make it happen. They get to set up their own labs with really awesome research and awesome purpose.”

Thomas considers it a great privilege to work under the leadership of Professor Scott Ayton, who is supportive of Thomas and encourages him to push himself.

“There was one time we were doing a completely different experiment,” Thomas recalls. “I experienced failure for two months and was really upset that we kept hitting a wall.

I nearly gave up but then Scott told me, ‘Thomas, give it one more shot’, and thanks to that advice, I made advancements, and it is now my research direction.

Our next generation of dementia scientists also work with a newfound hope.

Patricia highlights the advancement of dementia therapies. “At the time when we were taking care of my great aunt, there were no disease-modifying treatments in the market yet,” she says. “But now, things are picking up.”

Thomas explains that every three seconds, someone somewhere in the world is diagnosed with dementia. “And what is so mysterious is we don’t have a cure to stop the brain cells from dying.”

“So I hope that with my research, we can lay a foundation for future researchers to build upon to find a cure for dementia – and I hope one day, instead of three seconds, it would be four seconds, then five, then one hour, and then months. That is the hope.”