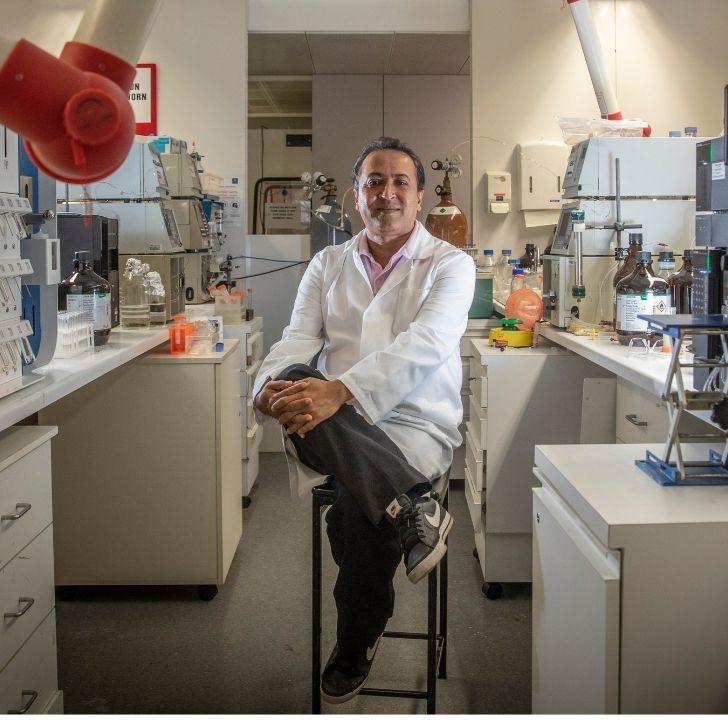

- Dr Abdel Belaidi has been studying Alzheimer’s disease at The Florey for the past 10 years.

- Four years ago, Dr Belaidi’s father, who lives in Morocco, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

- The diagnosis motivated Dr Belaidi to focus his research on treatments that aim to improve the quality of life for dementia patients and their families.

A “completely different picture” of Alzheimer’s disease

Dr Abdel Belaidi didn’t always know he was going to focus his career on Alzheimer’s disease research.

Ten years ago, Dr Belaidi was a postdoctoral researcher in Germany, investigating a rare sulphate toxicity disease that caused neurodegeneration in children.

Dr Belaidi and his team were successful in finding a cure and, for the first time, babies with this disorder have survived infancy and are now living normal lives.

At a conference in France, Professor Ashley Bush, researcher-psychiatrist based at The Florey, met Dr Belaidi and invited him to come to Australia to study a more prominent condition: dementia.

“Somehow I knew early that this is my field and this is where I want to stay,” Dr Belaidi said. He has now spent 10 years studying Alzheimer’s disease at The Florey.

Dr Belaidi began by working with Professor Bush to investigate the link between iron and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

But more recently, Dr Belaidi pivoted his research to focus on investigating the process of neuronal death in Alzheimer’s disease.

The motivating reason behind this change did not come from just anywhere. It came from his home.

“My perspective shifted profoundly when my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2021,” Dr Belaidi said.

Now aged 81, Abdel’s father lives in Nador, Morocco, where Abdel was born.

In 2016, the family had been noticing minor lapses in his memory that they hadn’t yet attributed to a disease.

“Timing was very important for my father,” Abdel said. “He prays at specific times during the day, and is always very punctual with his appointments, but we realised sometimes he was going two hours earlier than he should. This was probably the first time we realised something was not right.”

When Dr Belaidi first began work on Alzheimer’s disease, he was aware that memory loss is a main feature of dementia. However, life in the lab rarely confronted him with the everyday reality faced by a patient with dementia.

Abdel, who was living in Australia at the time, first heard the news from his sister.

“First it was a shock. It confirmed all the problems my father had, but when it happens to someone that you love, it is different,” Abdel recounted.

Because I am a scientist, I could accept that a disease was a part of life and treatments are available to treat symptoms. But I think the confronting part was seeing my father in person and the impact the disease had on him.

The first time Abdel came to Morocco to see his father, shortly after COVID, he described it as being confronted with a “completely different picture” of the disease.

His father, who had always been “very social, very chatty and very proud of his lifestyle,” would start getting ready for work in the middle of the night and heading to the front door, despite having been retired for years.

Mr Belaidi spent his life working at a post office for over 40 years – the only post office at that time in Abdel’s hometown of Nador, a small city on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

“So everyone knew my dad at the time because we had only one post office in the whole city,” Abdel said.

But the family grew concerned as Mr Belaidi gradually lost his sense of time and orientation. Abdel describes his father becoming “obsessed” with the front door, waking up almost 10 times each night to try and drive to work.

Today, the family locks the front door, knowing Mr Belaidi would not be able to remember where the house is to come back home.

The reality of the disease continued to sink in when Abdel’s father struggled to remember his name.

Abdel travels to Morocco every year with his children to visit his father and help care for him.

“In 2021, the first time he saw my daughter and son, he still played with them. But the second year, I realised he didn’t remember the names of my kids anymore,” Abdel recounted.

“I think the third year, which was last year, was the first time he didn’t remember me anymore. Sometimes he would feel that I was someone familiar, but he couldn’t quite understand that I was really his son.”

The biggest wish I had was that he will remember me, and my kids will have the opportunity to interact with him.

Throughout this time, Abdel’s father was prescribed several medications, mostly antidepressants. But Abdel found that the medications had short-term effects, and significantly affected his father’s sleep, leading to sleep disorders.

His father also gradually needed help in everyday tasks such as eating and drinking – losing the ability to discern things such as differentiating drinking water from oil, or responding to a phone call.

“It was not just memory loss,” Abdel explained. “Think of it as the brain itself shutting down slowly.”

Ultimately, the experience motivated Abdel to target aspects of the brain with the aim of bringing small benefits to a patient’s lifestyle, that may have a big impact on their life and the people around them.

My personal story with my father taught me to see a clinical aspect that a normal researcher may not be confronted with in their daily life.

Seeing that impact on a patient’s life is what pushed Dr Belaidi at the end to reconsider the objective of his research.

Today, Dr Belaidi forms part of The Florey’s Dementia Mission, investigating the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, which has the potential to dramatically improve treatment for people with all subsets of Alzheimer’s disease.

Ultimately, Dr Belaidi’s research focuses on slowing down the process of neurodegeneration in dementia – to help improve the daily life of a patient and their family members.

We believe that if we find additional genetic or lifestyle factors that may slow down the disease, it will be effective in having a better outcome for patients that are suffering from the disease.

Dr Belaidi also believes it’s important to have conversations about dementia as a disease more openly.

“Sometimes, Alzheimer’s disease is not seen as a disease, as it should be. My father didn’t want to accept that he had a problem,” Dr Belaidi said. As a result, his father and the people around him would try to hide the disease.

“But if my father was better prepared for it, it would have been less of a shock for all of us, and he could have made arrangements to better his quality of life.”

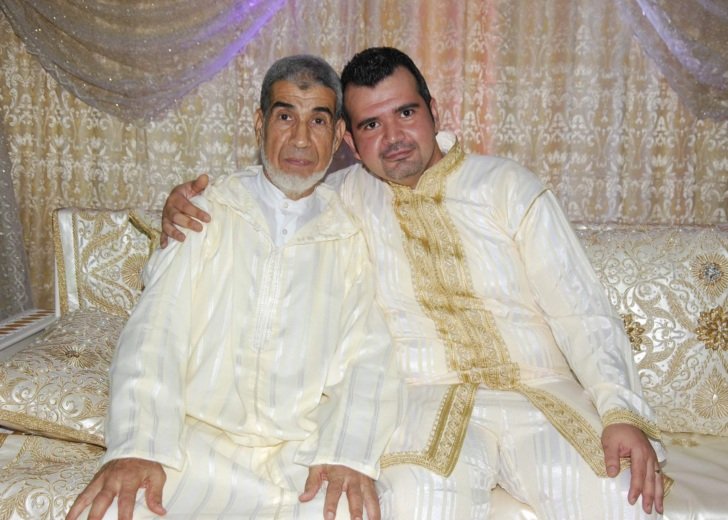

Looking back at the photo taken with his father, Dr Belaidi finally adds, “This is one of the beautiful, beautiful pictures that I have in my memory.”

“I always had this fear that my father wouldn’t live long enough to be present in my wedding, but he was – and this is one of the reasons why it’s the best day of my life. He was very happy, he danced a lot. I remember that day.”