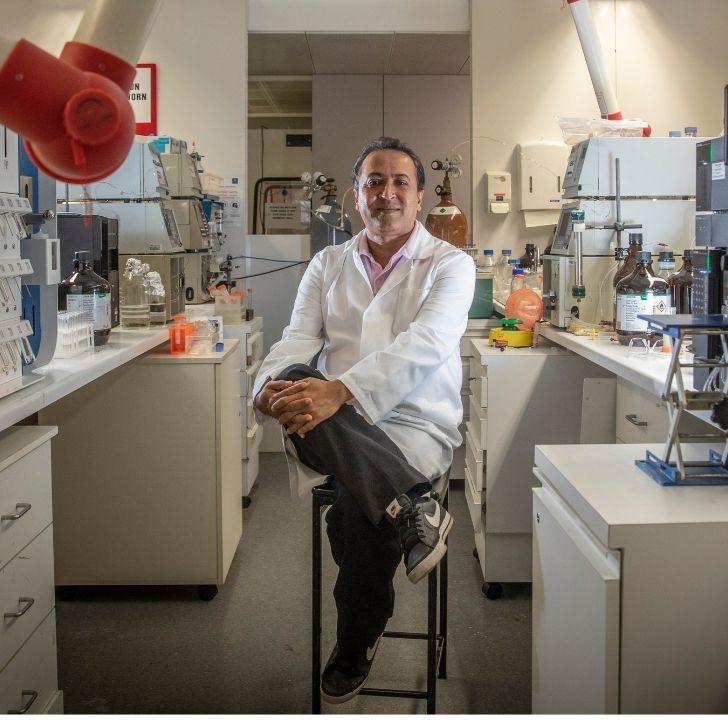

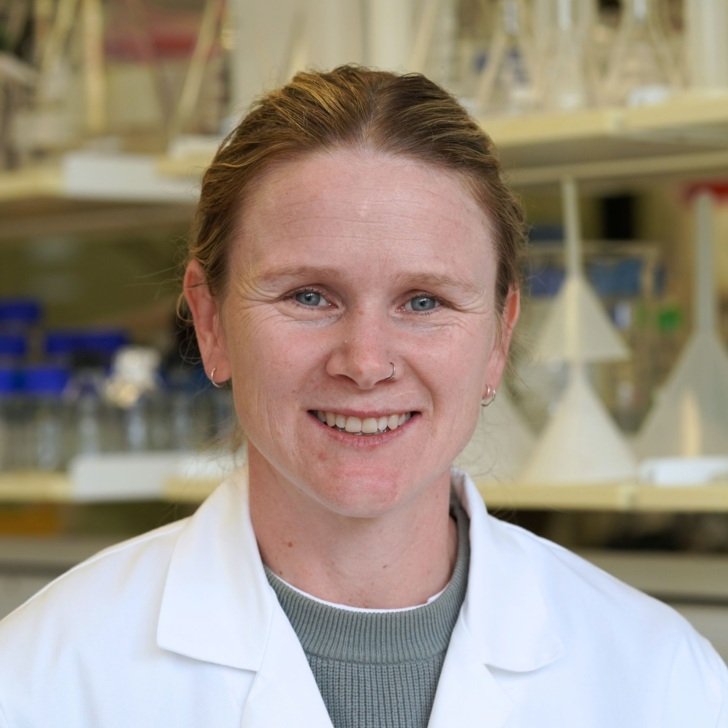

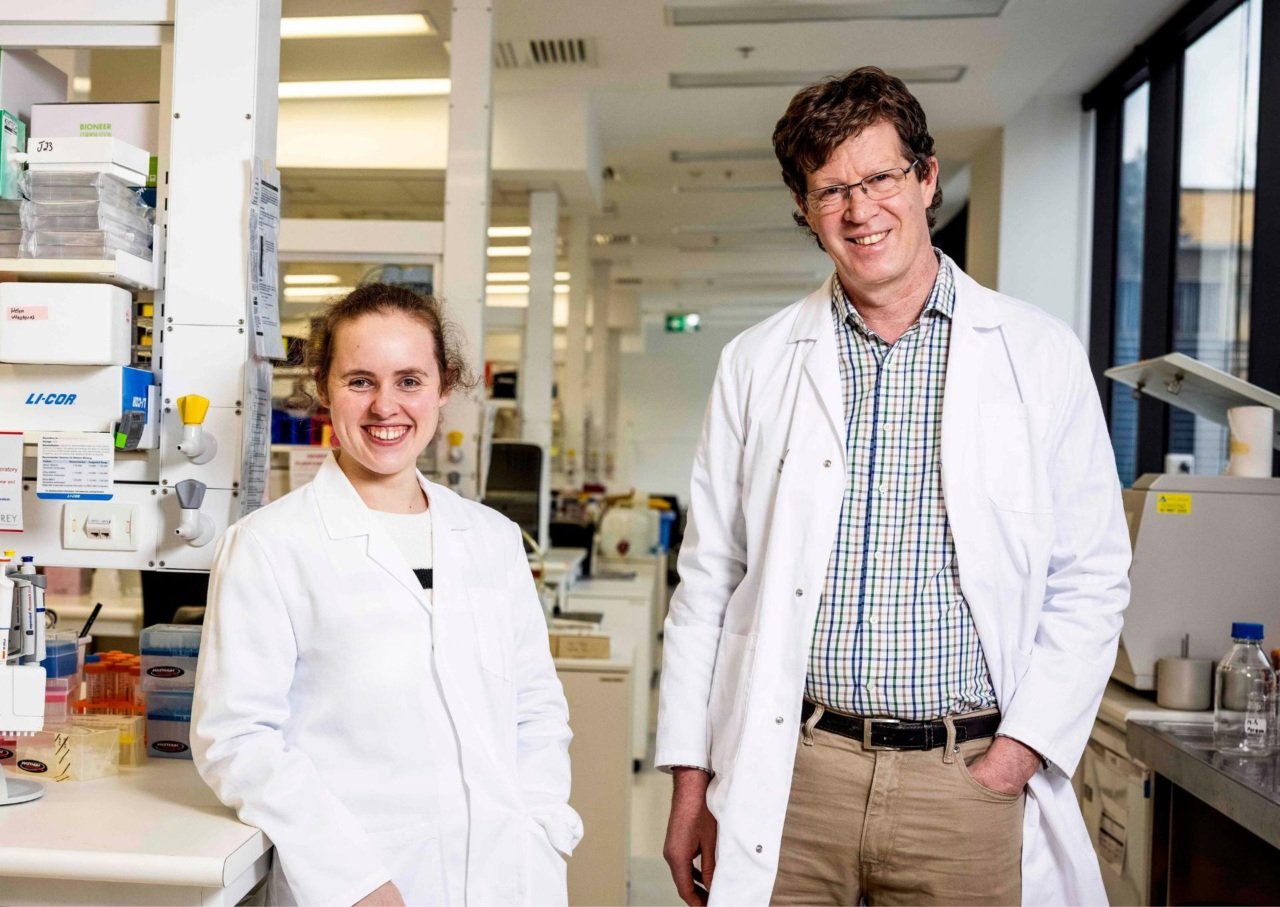

- Dr Lauren Bleakley is a postdoctoral researcher in The Florey’s Neurophysiology of Excitable Networks Laboratory, led by Professor Chris Reid.

- Dr Bleakley first came to The Florey via an Open Day as a University of Melbourne undergraduate student.

- Her advice for students looking to pursue a career in science is to gain lab experience as soon as possible.

A chat with Dr Lauren Bleakley

Q: Lauren, thank you for speaking with us. Do you want to start by introducing yourself and telling us about your journey at The Florey?

Hi! My name’s Lauren, and I’m currently a postdoctoral researcher here at The Florey. I’ve been interested in science for as long as I can remember, and I became particularly interested in the brain when studying psychology at VCE.

When I was doing my bachelor’s degree, I initially thought I wanted to major in psychology. Then I figured out that the parts of psychology that I was most interested in were neuroscience. So for my third year, I transferred across to majoring in neuroscience.

Q: Why neuroscience in particular?

The brain is one of the new major frontiers of science in our time. It is so unknown for something that is so critical. We’re all walking around with brains in our heads, but a lot of the time we don’t know how they’re doing what they’re doing.

Neuroscience is really at the centre of a combination of curiosity and helping people.

When I decided that I wanted to be a scientist, I wanted it to be in a field that was cutting edge – something new that we didn’t really understand. Also, I was always drawn towards biological sciences, especially the translational element of helping people.

Q: How did you make your start at The Florey?

I actually started at The Florey through an Open Day. I came to The Florey’s Open Day in 2016 looking for an honours project as a Melbourne University student at the time, and that’s where I met Professor Chris Reid who went on to be my honours and PhD supervisor.

Some advice that I’d been given was that when you’re an honours student, you are really learning how to be a scientist. So it’s really important to choose your honours lab based on the supervisor and the lab itself – the people around you.

I spoke to several potential supervisors and clicked with Chris at the start. I also spoke to several other people from his lab who were welcoming and enthusiastic. I got a sense that I could work well in their team.

Q: Could you talk to us about your area of research in more detail?

My main area of research is genetic epilepsy. This covers genetic mutations that cause brain cells to malfunction and fire too much or in sync with each other, and that causes seizures.

There are two prongs to how we look at this. Firstly, looking at how these mutations cause epilepsy at a fundamental level: How do they disrupt neuron function and lead to epilepsy? Second, what are the best ways of treating these conditions?

The reason that I got into science originally was because I wanted to make discoveries that helped people.

I draw a lot of intrinsic motivation from knowing that my work is going to have an impact for people. Translational research – that is, research applied towards treatments with an idea to help people with disorders – feels very close to that.

Q: Some of your work with Professor Chris Reid has also led to some real change in the lives of families and children with epilepsy. Could you share some of these stories?

I’ve been honoured to meet some wonderful, inspiring families who have young children with severe forms of genetic epilepsy.

In particular, I’ve gotten to know the families of two young girls: one named Ebony, and one named Fern. Both of their families have inspired me with the amount of trust they’ve placed in our lab to do this work, which provides them with hope that we might be able to help their young daughters.

Some of the work I’ve done discovered how genetic mutations that both of these girls have caused their seizures. We’ve also been able to look at the best treatments for those epilepsies.

As a result, both young girls are now living healthier lives. Their epilepsies are better controlled than they used to be, and in Fern’s case, she’s completely seizure-free as a result of the work we’ve done here at The Florey.

Q: That’s a beautiful story and must have been a significant moment in your career.

It truly was. I went into science to make discoveries that help people, and when I began, I thought that would be a life-long endeavour and that it might take an entire career to have such an impact.

But the fact that I’ve already been able to do that is my proudest achievement. It has lit the fire in me to know that it is possible, and inspired me to continue doing research that can make a difference in more people’s lives.

Real people are really the driving force of science.

For me, a lot of the persistence through the difficult times comes from the real people behind it. They’re the motivating factor when you’re in the lab late at night and you’ve had a day where everything goes wrong – which does happen! That’s life in science.

But on those days, I thought, “There are a couple of kids out there that I know could be having better lives if we manage to make this work. So we’re going to make this work.”

Q: What is your best piece of advice for those who wish to pursue science as a career, including students who want to study neuroscience?

The first one would be to get yourself in a lab as soon as you can.

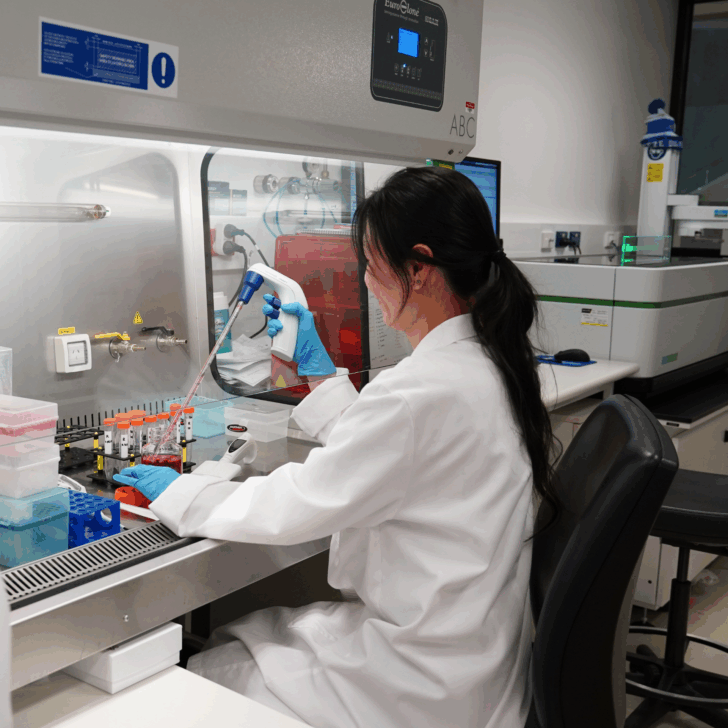

Labs are exciting places, but it will be quite different from high school or undergraduate labs because we’re usually doing experiments that nobody’s ever done before. While you might have a hypothesis, you often won’t know exactly how things are going to turn out.

So I think it’s difficult to know if the lab environment is for you or not until you’ve experienced it.

My number one piece of advice for potential students in any field of science is to get in touch with a scientist. If you know somebody who’s doing work in a field that you’re interested in, see if you can spend some time in their lab.

My second piece of advice is more directed to students who are looking for particular labs or choosing their supervisors. Look not only at the supervisor and the project, but also at the broader team.

The people around you are really important, and no more so than when you’re a student, when you’re new, and you’re going to be needing more advice and support as you’re learning.

So speak to other people in the lab and see if you think that that group dynamic and environment would be a good fit for you.

Q: Finally, do you have anything else to share from your experience at The Florey?

If you’re interested in the brain, then The Florey is the place to be. You are constantly surrounded by scientists who are making groundbreaking discoveries frequently, so you’ve got inspiration around you whenever you walk in the door.

Also, The Florey gives you access to cutting-edge equipment, infrastructure and support that you’re going to need to build a career, build your own ideas and make your own discoveries.