- Iron deficiency or overload are detrimental to the health of billions of people worldwide, yet today’s iron tests use unreliable, decades-old technology.

- Inaccurate iron testing leads to misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis both of which can profoundly impact patient health and wellbeing and governments’ health budgets.

- A new test called FeBI, that uses quantum technology to accurately test iron, is being developed by a team of Florey, University of Melbourne, and CSIRO researchers.

Australia’s Economic Accelerator (AEA) funding for Florey project

Quantum sensors that will revolutionise diagnosis and management of iron disorders, move to its next phase, thanks to AEA funding.

An estimated 1 in 5 women (and 1 in 20 men) in Australia are iron deficient, but many remain unaware due to inaccurate and outdated blood tests.

Iron deficiency can cause fatigue, poor concentration, a weakened immune system, poor sports performance, pregnancy complications and – left untreated – life-threatening anaemia.

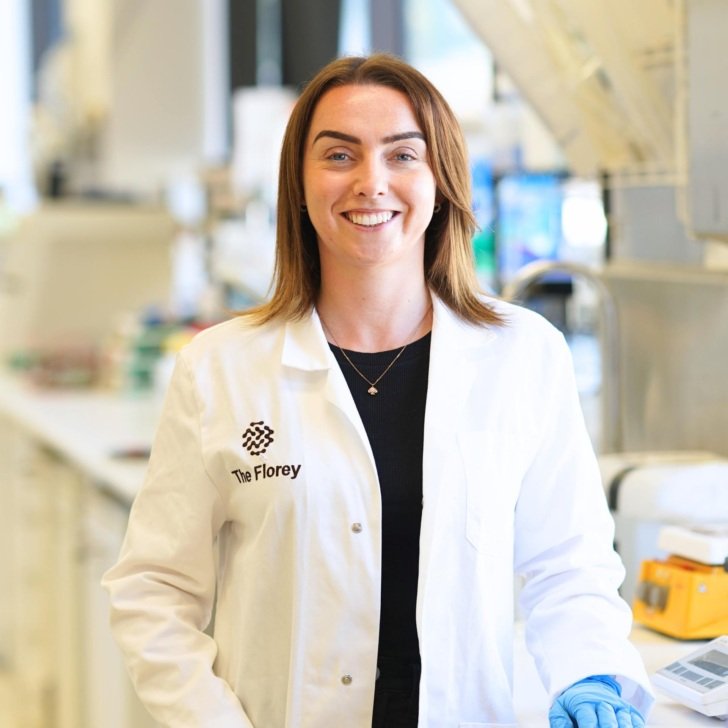

“Inaccurate iron testing has the potential to cause major health consequences, for women in particular,” said FeBI founder and project lead, Florey Associate Professor Gawain McColl.

Standard iron tests measure how much ferritin, the body’s primary iron storage protein, is contained in a blood sample. However, this indirect test of iron storage is often misled by other underlying health conditions, like inflammation.

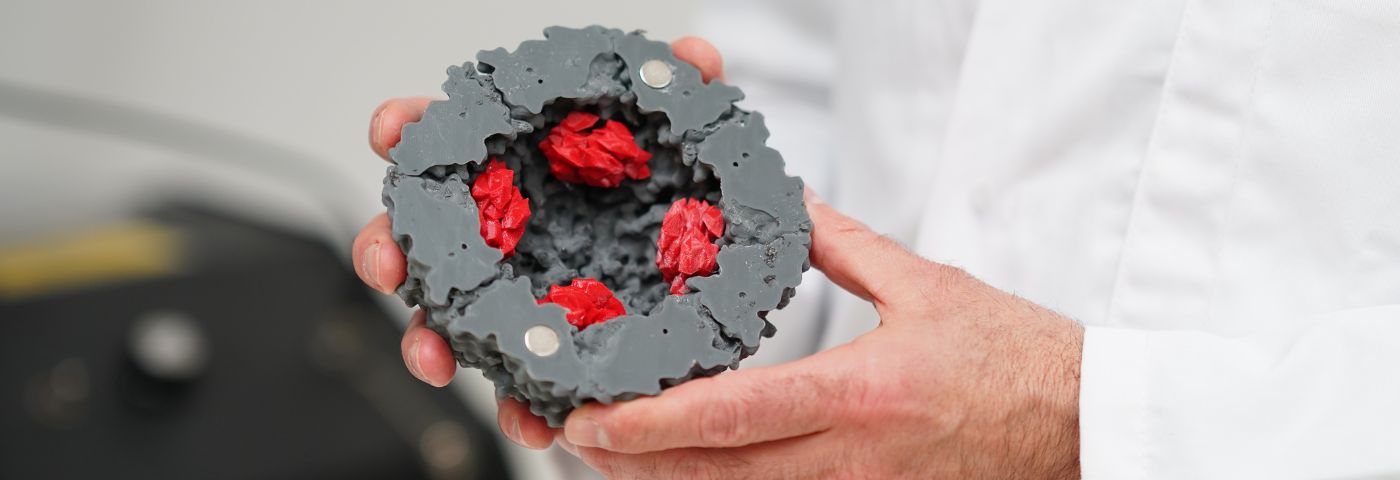

Associate Professor McColl said the FeBI (Ferritin Bound Iron) technology that is under development uses diamond-based quantum sensors to measure the magnetic fields produced by iron atoms contained in ferritin.

FeBI gives an extremely accurate readout of iron levels within ferritin. The problem with current testing is that common health conditions such as diabetes or obesity elevate people’s ferritin but not their iron.

Because blood tests detect all ferritin, regardless of whether it is iron-laden or iron-empty, they fail to diagnose many iron-deficient people because they have underlying health conditions,” he said.

Associate Professor McColl said such inaccurate results delay correct diagnosis, often meaning more diagnostic tests – as GPs do their best to help patients – and adding challenges to clinical decision-making.

“All of these extra treatments and diagnostic tests are a burden on the Government’s health budget,” he said.

“Our quantum sensing technology provides a unique opportunity to develop world-leading medical technology. We are working hard to deploy a prototype into pathology laboratories to assess clinical samples. It will mean better outcomes for patients and healthcare systems.”

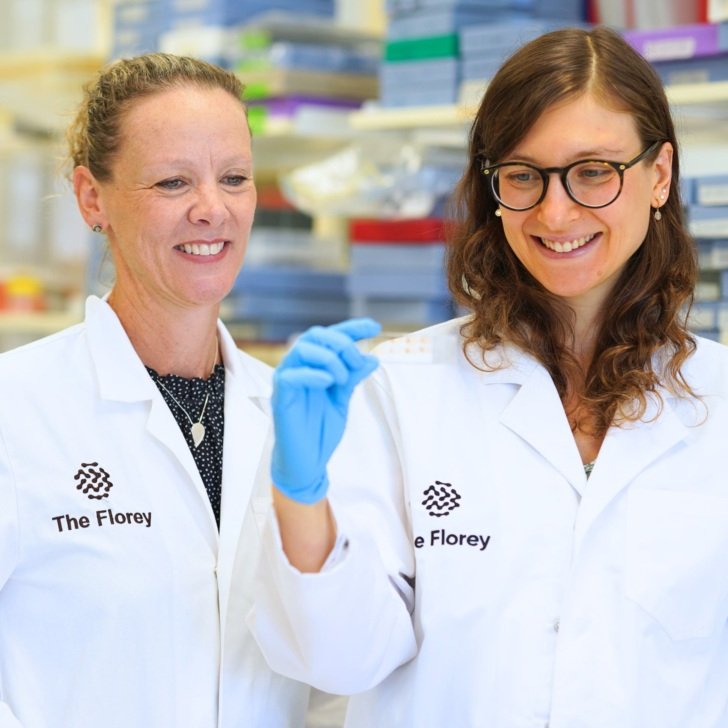

The project is a collaboration between Florey researchers and physicists based at the University of Melbourne and CSIRO. It has benefitted from entrepreneurial mentoring support from TRAM (Translating Research at Melbourne).