- New research has discovered a brain pathway that drives stress-related eating.

- This research helps to explain what drives emotional overeating in women.

Around 20 per cent of us react to feeling stressed or experiencing negative emotions by eating. That figure makes what’s called ‘stress eating’ remarkably common in the adult population.

This disordered eating behaviour, also called binge eating, involves consuming large amounts of food in a short amount of time. In Australia, the prevalence of this type of eating behaviour has more than doubled over a decade – with research estimating that up to eight per cent of Australians now binge eat.

Binge eating and loss-of-control eating are highly associated with obesity and, because of this, these disorders cost Australia an estimated AU$11.8 billion annually.

Whatever label is used – ‘comfort eating’ or ‘emotional eating’ – our new research in mice models shows that a particular pathway in the brain helps explain why females suffer disproportionately from this type of eating, as well as associated disorders like binge-eating or bulimia nervosa.

Women and disordered eating

Previous research has shown that eating disorders are profoundly influenced by gender, with reported estimates of the male-to-female ratio ranging from 1:4 up to 1:9.

Subclinical disordered eating behaviours (including subjective binge eating or compulsive eating) as well as anxiety and depressive symptoms are also more prevalent in women.

This can mean that negative emotions including stress, anger and low mood are more likely to drive overeating in women.

But the poor understanding of the precise biological mechanisms underlying this sex-specific behaviour likely underpin the high failure rate of current treatments for overweight and obesity that is driven by overconsumption.

So, we looked at the brain’s neural pathways for clues.

The brain pathway that drives emotional eating

To date, we’ve known very little about the precise brain circuits that drive emotional eating in women. This is partly due to the lack of appropriate models and partly due to the historical lack of focus on women in research.

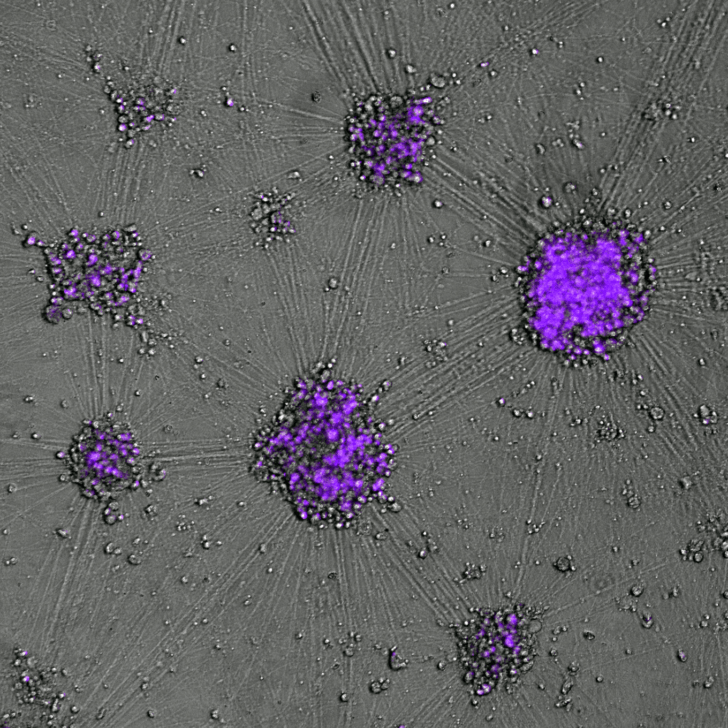

To understand more, our team developed the first model of ‘emotional’ stress-induced binge eating in mice. Our model didn’t use caloric restriction to induce binge eating, instead, mice could smell the desirable food for 15 minutes before being able to consume it.

Our study showed that, like humans, female mice displayed pronounced binge-like behaviour after they were exposed to stress, where male mice didn’t.

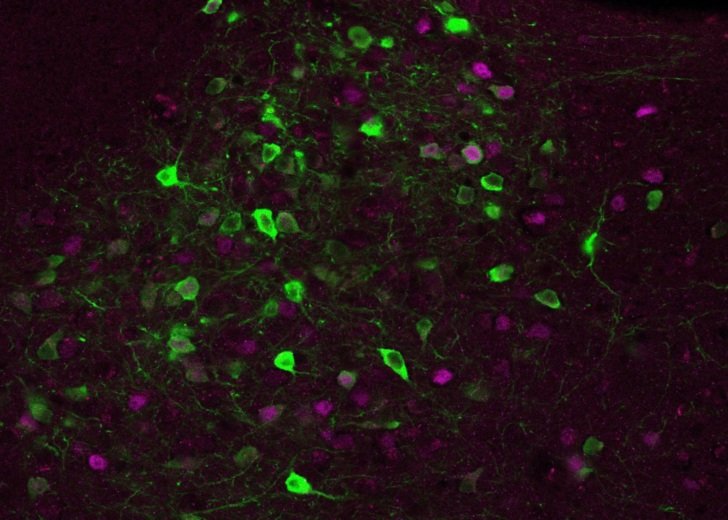

We focused on an area of the brain called the insular cortex (insula), which we know is responsible for detecting internal bodily states like blood pressure and oxygenation, the motility of the digestive system, the timing and strength of the heartbeat, as well as pain, hunger, nausea, tickle, itch and many more bodily sensations.

The insula is also thought to be involved in feelings and emotions and, more so in women than men, is activated in response to food cues, particularly for women with a higher body mass index (BMI).

Our research identified a pathway connecting the insula to a part of the brain called the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (or PVT), which enables signals to pass between these areas.

When this pathway was blocked using a technology called Designer Receptors Activated Only by Designer Drugs (or DREADDs), the mouse model’s binge eating was reduced.

The fact this happened highlights the importance of this pathway for this behaviour.

Other research has shown that the PVT is a key region of the brain for reward-motivated behaviour, historically studied in drug addiction and food reward.

But our research has now shown for the first time that it is also involved in stress-driven eating in mice.

Although these studies can’t be conducted on humans, we can infer that the human brain is likely to respond in a similar way – as these sort of behaviours are very similar between the two species.

Our discovery also helps to dispel the myths that societal pressures or psychosocial factors are the only factors in stress eating and confirms there is a biological factor involved.

Reducing stigma and BMI

Identifying the neural pathway in this type of eating behaviour will hopefully contribute to preventing the estimated four million global deaths annually from high BMI.

There are currently very limited treatments available for people who struggle with emotional or stress-induced binge eating; things like cognitive behavioural therapy has shown success but can be cost prohibitive.

Stimulant medication is unsuitable for many people due to the susceptibility for abuse, sleep issues, or for those with cardiovascular issues. As such, there is a huge unmet need for improved therapies.

One possibility may be repurposing anti-obesity drugs that mimic the actions of incretin hormone GLP-1. For example, the diabetic prescription drug, semaglutide, known better as the much-discussed Ozempic.

These medications increase feelings of fullness and decrease appetite, so it’s possible they may also reduce stress-induced binge eating.

The vast majority of women who suffer from emotional eating do not currently seek help or treatment for it. It is estimated that only 19 to 36 per cent of people with disordered eating will get treatment, meaning many women are left underdiagnosed to suffer in silence.

We hope our work will help to reduce the stigma around the idea that people who overeat are just weak and can’t control themselves, hopefully encouraging them to seek help sooner.

The research team will now move into its next phase of developing new therapies.

This will include uncovering specific targets that can be harnessed for drug discovery, as well as seeking to understand why women and men are biologically different in their eating response to stress and emotion.

If you or anyone you know needs help or support, in Australia, you can contact the Butterfly Foundation on 1800 ED HOPE.