This year marks 30 years of Australia’s longest running disease registry and biorepository: The Australian National Creutzfeldt-Jakob (CJD) Disease Registry at The Florey.

The history of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) reads like an unravelling mystery novel. From mourning rites and unknowingly contaminated treatments for short stature and infertility, to the globally notorious “Mad Cow disease” – it’s an odyssey of epidemiological and scientific wonders and progress.

Human prion diseases

In the early 1920s, two German doctors Hans Creutzfeldt and Alfons Jakob independently reported cases of a mysterious, rare and always fatal human brain disease.

For many years CJD was thought to be caused by a ‘slow virus’.

The aetiology or causes of the disease baffled scientists, until 1982 with the groundbreaking discovery that CJD is caused and can be transmitted by a misfolded protein, which he called a prion (derived from ‘proteinaceous infectious particle’). That work won Stanley Prusiner the 1997 Nobel prize.

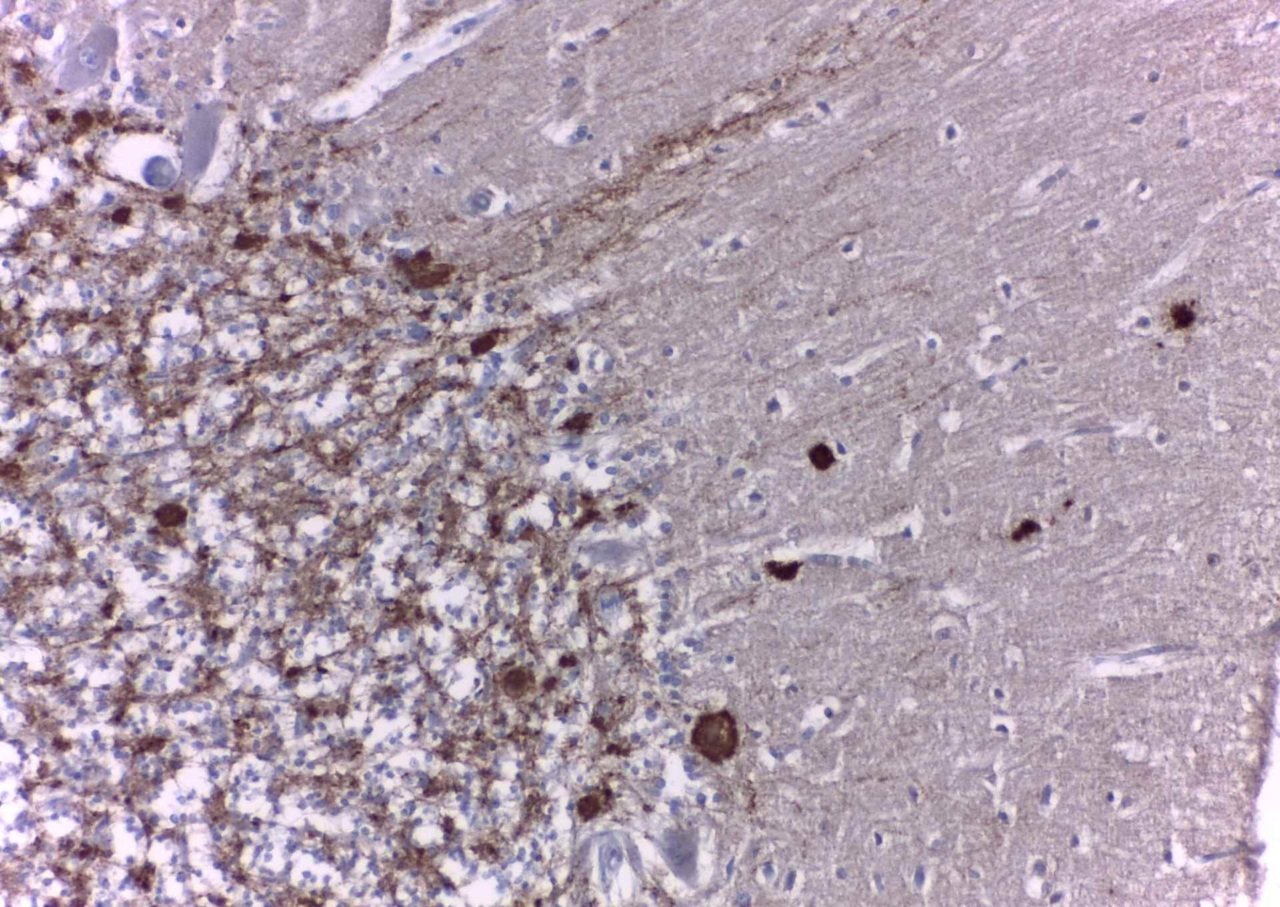

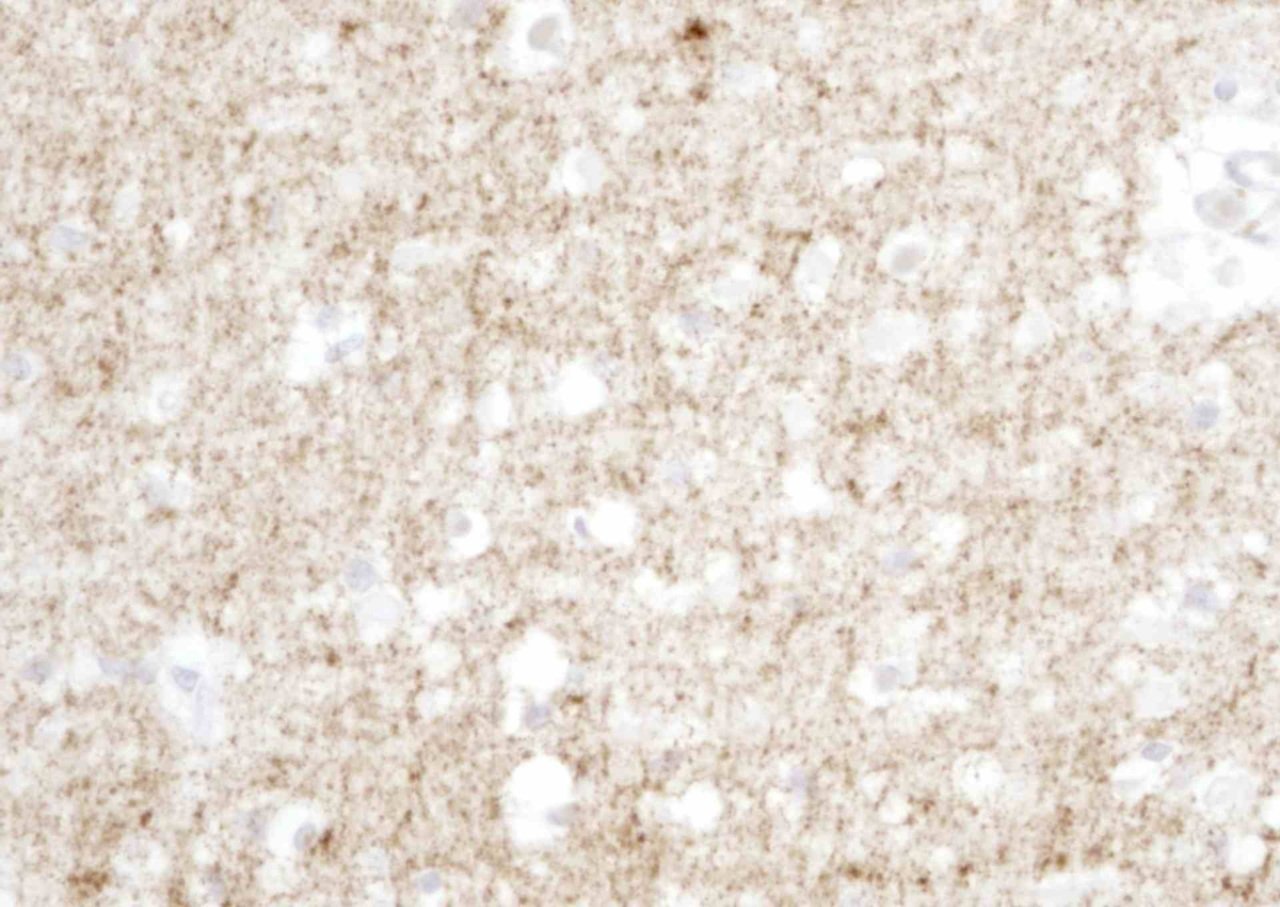

We now know that this misfolded prion protein accumulates in the brain causing neurons to degenerate and die, resulting in the spongiform (riddled with holes) appearance of the affected brain tissue. Procedures that kill bacteria or viruses can be innocuous to prions, making them often difficult or impossible to destroy with established disinfection procedures.

In Australia, between 60 and 80 persons are diagnosed each year with suspected CJD. About 85 per cent of cases are sporadic, meaning there is no clear-cut reason for the illness.

Prion diseases can occur genetically as familial CJD, Fatal Familial Insomnia and Gerstmann-Straeussler-Scheinker Syndrome, or they can be acquired through medical procedures (iatrogenic CJD) or diet (variant CJD) .

Most people affected are elderly and typically experience rapid neurological decline, presenting most often as dementia with gait disturbance and motor dysfunction, leading to death within four or five months.

“There is no cure or disease-modifying treatment,” Professor Collins said.

Kuru

Prion diseases have been present in the Pacific region for decades through Kuru, now considered an extinct disease.

Kuru means ‘shaking or trembling’. Australian rangers first documented this strange and fatal neurological disease in the mid-1950s in remote tribes of Papua-New Guinea, under Australian administration at the time. Kuru was restricted to the Fore-speaking people of the isolated Eastern Highlands. It was the leading cause of death amongst the Fore women, where men outnumbered them by three to one.

The dedicated work of the Australians, Michael Alpers and Vincent Zigas and American paediatrician Carleton Gadjusek, working from Melbourne, discovered the link between Kuru and cannibalistic funerary rituals, wherein women and children consumed brains and other organs of prepared bodies from deceased relatives while men mostly consumed the prepared skeletal muscle.

This cultural practice was a mark of respect and was performed to honour the dead. When the practice stopped, so too did the spread of Kuru.

‘Mad Cows’ and variant CJD

‘Mad Cow disease’ (bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE) is the brain-wasting zoonosis (a disease that breaches the species barrier from animal to human) that forced British farmers to cull millions of cattle. BSE caused cattle to have trouble walking, lose weight and die within a few weeks. The disaster was caused by the then common practice of farmers feeding calves meat-and-bone meal that contained the remains of cattle affected with BSE; the practice was eventually banned in 1988. By 1992, BSE was largely conquered following the instigation of various food safety measures, but the human catastrophe was only just beginning.

Through incompletely understood factors, a small fraction of people who had eaten BSE-contaminated products contracted variant CJD, a neurological illness mostly affecting young people, always fatal and appearing reminiscent of BSE. This form of CJD caused the deaths of 233 people worldwide.

The need for national surveillance in Australia, enter The Florey

From 1988 to 1991 four young Australian women died from CJD. All four women had undergone fertility treatment through the Australian Human Pituitary Hormone Program (AHPHP), which ran from 1967-1985 and which also provided treatment for short stature. Their deaths were part of a ripple of CJD cases that did not fit the disease phenotype of a neurological condition of advanced age.

As it was common practice around the world at the time, the AHPHP used hormones extracted from the pituitary glands of human cadavers. Efforts were made to ensure the glands posed no danger, but at that time prions had yet to be identified and the associated dangers were unrecognised. The program was suspended in mid-1985 due to the risks it posed.

As a result of the program, 2952 people in Australia were notified that they may be at risk of developing CJD in their lifetime.

This medical tragedy prompted the establishment of the Australian National CJD Registry (ANCJDR) and the CJD Support Group Network (CJDSGN) in 1993. The ANCJDR continues to provide diagnostic testing services, national surveillance and epidemiology and expert advice to the medical community for this group of rare and transmissible diseases. With 30 years of continuous operation, it is also the longest standing disease registry and biorepository in Australia, collaborating with numerous international prion research and surveillance centres.

The ANCJDR is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and is hosted at The Florey, The University of Melbourne. The CJDSGN, also funded under similar arrangements, provides support services to families affected by prion diseases and the at-risk cohort.

From tragedy to hope

A diagnosis of CJD or other prion disease is usually accompanied by dread, an illness considered without hope for any form of meaningful medical intervention. Nevertheless, over the last 30 years there has been prodigious progress in prion research to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and our understanding of the underlying disease mechanisms.

In 2020, the University College of London, under the leadership of John Collinge, successfully embarked on the first in-human assessment of anti-prion antibodies to reduce aggregation of prion protein in brain tissue.

Researchers like Professor Collins and colleagues at The Florey continue to actively investigate possible treatments for CJD and to turn tragedy into hope.