- Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive neurological disease that affects 33,000 Australians and three million people worldwide.

- About one-third of people living with MS have progressive disease, which current treatments do not address effectively.

- Florey research identifies how inflammation may contribute to MS progression, paving the way for new treatment possibilities and research avenues.

Neurons located in MS brain lesions have a faster mutation rate than normal neurons

For the first time researchers have identified that inflammation – long associated with MS – appears to cause increased mutations linked to MS progression.

They studied MS brain lesions, visible as spots on MRI scans, which are areas of past or ongoing brain inflammation.

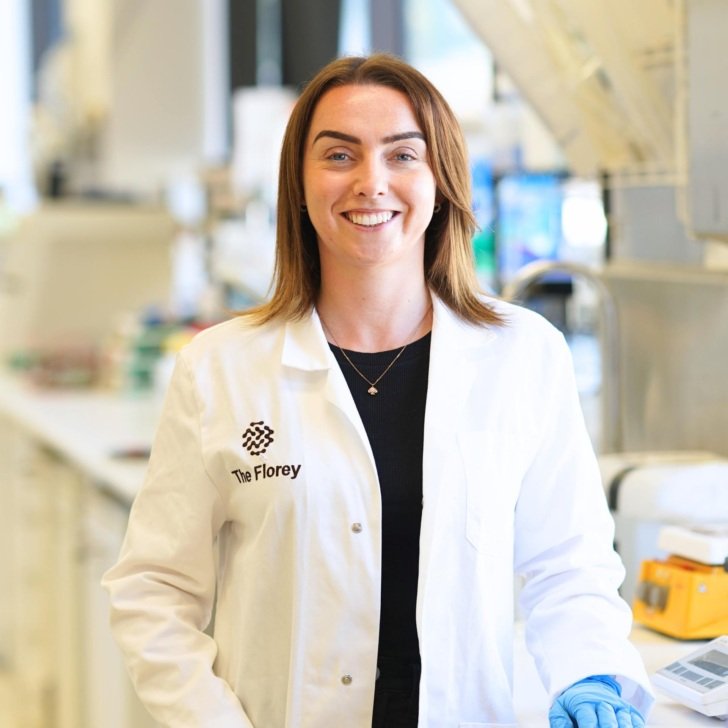

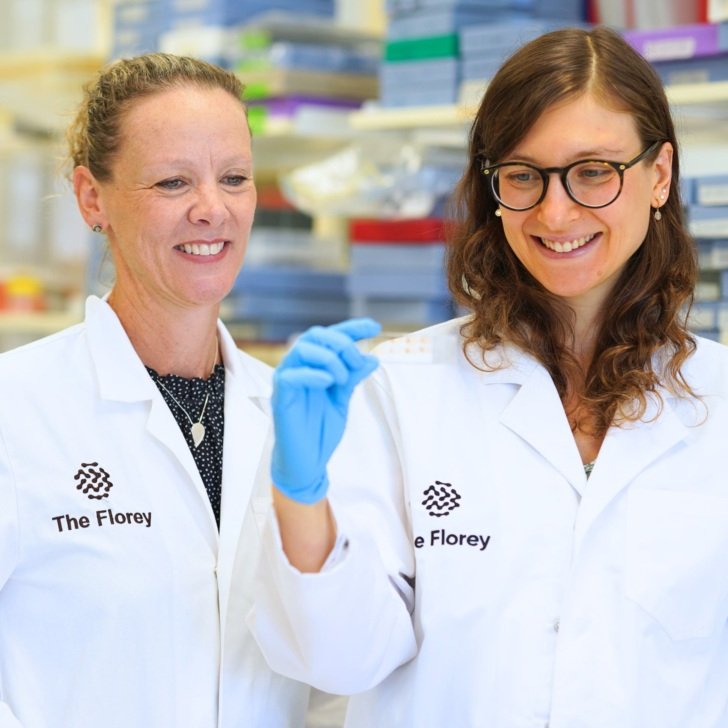

Florey Associate Professor Justin Rubio, Head of The Florey’s Neurogenetics Group led the research published today in Nature Neuroscience.

Associate Professor Rubio said: “Our research suggests that inflammation in the brain of people with MS causes mutations in neurons, which may contribute to progression.”

The team from the Florey Institute and University of Melbourne focused on somatic mutations, which are not inherited but occur over time in cells during ageing. Mutations can disrupt a cell’s normal function or survival.

The researchers compared mutations in neurons from the brains of 10 people with MS and 16 people without MS. They found that neurons in non-lesion areas and the brains of people without MS accumulated 17.7 mutations per year, while neurons in MS lesions accumulated 43.9 mutations per year.

This means that by age 70, neurons in MS lesions have around 1,300 more mutations than normal neurons.

Bioinformatician and first author on the paper, Dr Allan Motyer, was involved in the research during his time at the University’s Melbourne Integrative Genomics and School of Mathematics and Statistics.

“Not only did we find there are more mutations in MS lesions, but they are also of different types to those seen in normal ageing, indicating a distinct molecular process causes mutations in MS,” Mr Motyer said.

Associate Professor Rubio and team are working to build on this important finding and investigate new treatment avenues for progressive MS.

Co-author on the paper, Florey researcher and practising neurologist Professor Trevor Kilpatrick said this research was significant because it was the first to show that inflammation could be connected to the death of neurons in MS via accelerated mutation of the genetic code.

Once we know for certain what molecular disruptions kill the neurons, we hope to find a way to save them, or keep them alive for longer to minimise progressive disease.

It’s not a treatment for progressive MS yet, but it brings us closer to one.

The researchers are grateful MS Australia and to all families who donated the brain tissue of their loved ones to science, enabling this research to take place.

The study involved researchers from University of Sydney, BGI-Australia and The China National Gene Bank.