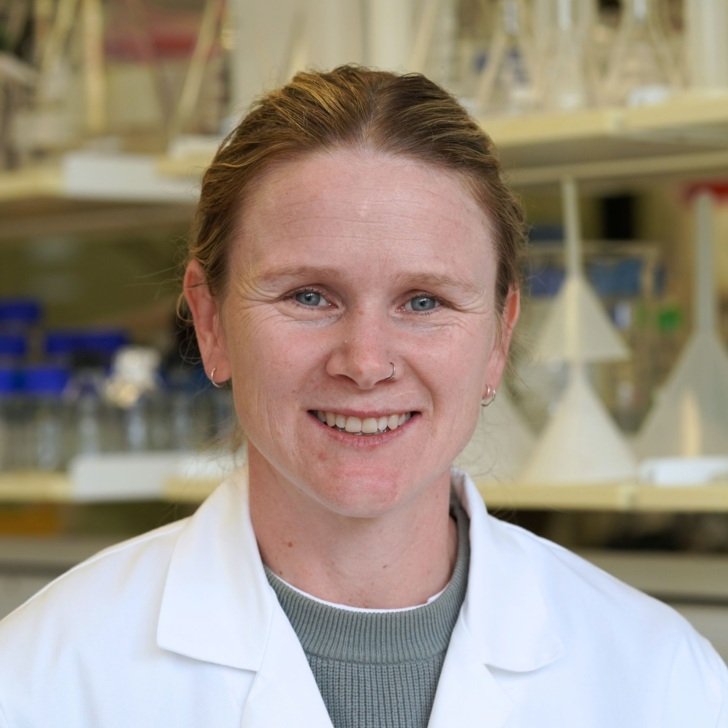

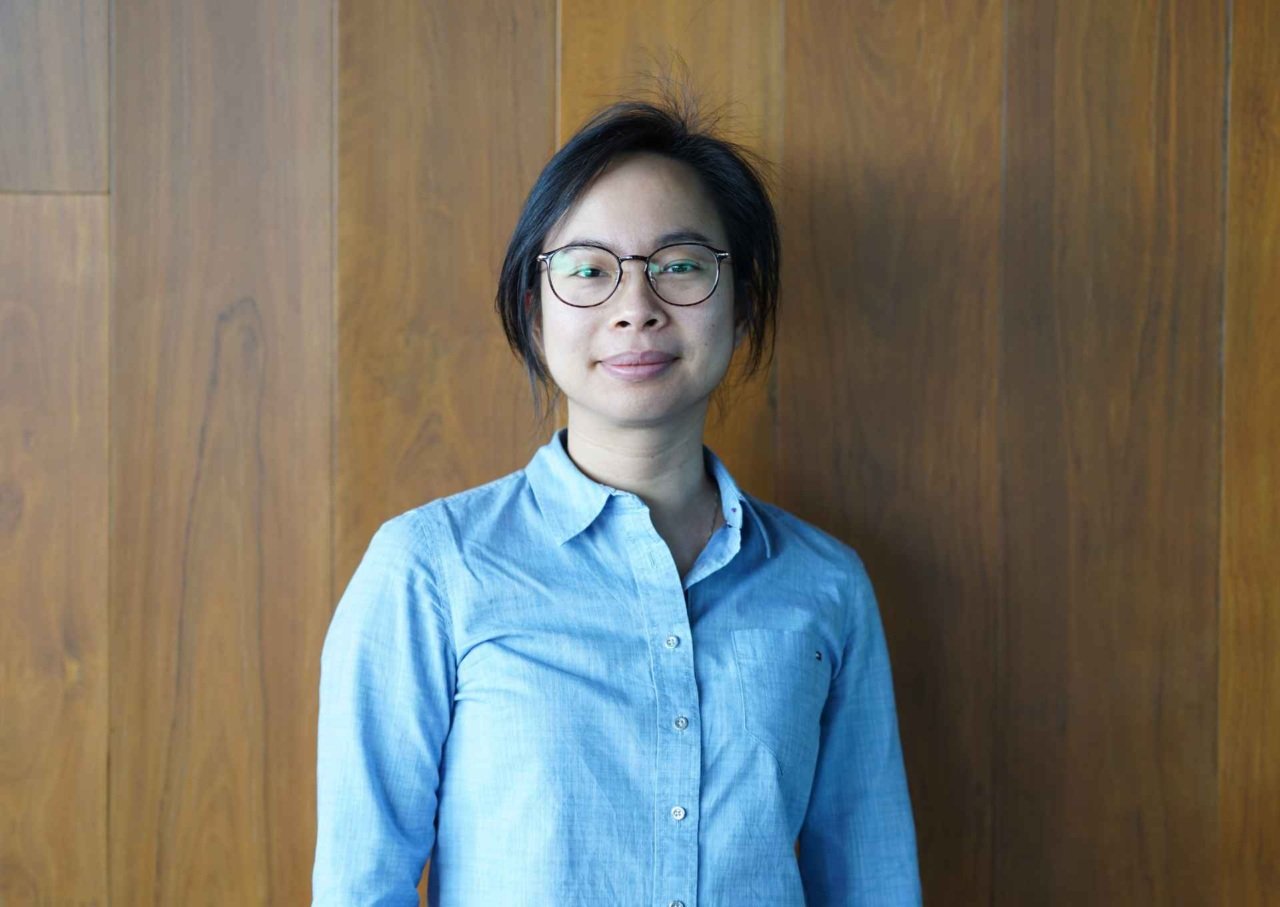

Florey researcher Dr Melody Li is leading work to find a treatment to help children with severe childhood epilepsies, a rare form of the disease which can present in babies just a few days old.

In Australia, an estimated 1 in 150 people live with epilepsy, a complex neurological disorder that can cause seizures and developmental delays. Severe childhood epilepsy affects approximately one in 590 children under 16 years of age and can cause severe and frequent seizures.

The particularly devastating form of the disease that interests Dr Li is Developmental Epileptic Encephalopathy (DEE), which often lowers the child’s life expectancy and causes severe intellectual and physical disability.

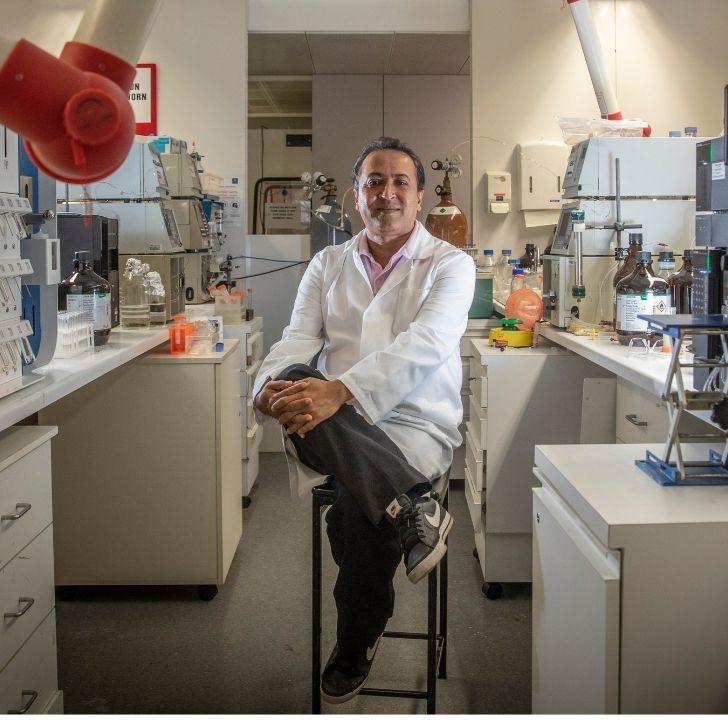

Dr Li began research with Professor Steve Petrou during her honour’s year at The Florey.

Thirteen years later, a promising treatment resulting from Dr Li’s research has just begun human clinical trials in the United States.

I find the brain fascinating in its complexity. There is still so much we don’t know about how it works. But we don’t just study the brain, we study the impact of neurological conditions on people – and I’m so grateful for all of the patients and families affected by severe childhood epilepsies for their support of our work.

Dr Li, a senior research officer in the Ion Channels and Human Diseases group at The Florey, is investigating a potential treatment for children with DEE caused by mutations to a gene called SCN2A.

The SCN2A gene contains instructions for a key receptor in the brain. Receptors are a part of the body’s molecular machinery that enable cells to communicate with one another. Mutations in SCN2A are strongly associated with several neurological disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia and severe childhood epilepsy.

Dr Li says a group of mutations in SCN2A can result in hyperactivity of the receptor, so the person’s brain cells fire more rapidly and more synchronously, leading to severe epilepsy in infants as young as just a few days old.

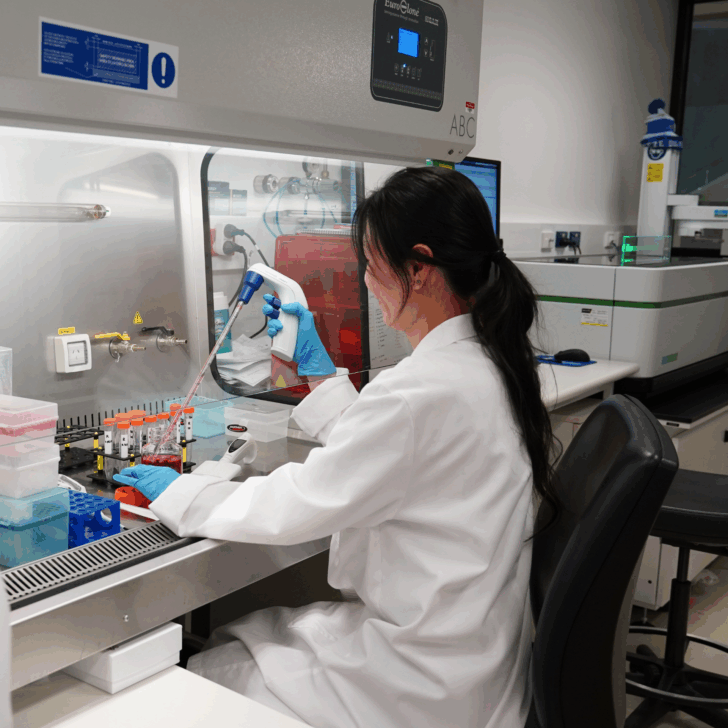

Working with mouse models, Dr Li examined a promising treatment called antisense oligonucleotides (ASO), which are DNA-like molecules. Together with other Florey scientists, clinical and commercial collaborators, her work identified a way for ASO to specifically bind to SCN2A and reduce SCN2A activity in cells, thus removing the key driver of the disease.

Pre-clinical studies of this treatment conducted in mouse models showed promising disease reversing effects, and a safe, therapeutic dose range was determined. After obtaining FDA approval, the ASO treatment has now moved onto the clinical trial, looking into the safety and effectiveness in patients with early-seizure onset SCN2A epilepsy.

“We still have a lot of work to do advance this molecule down the clinical pipeline. I’m excited to that we’re making progress towards treating and providing hope for people affected by this devastating condition,” Dr Li said.